Exploring Francis Bacon: Revealing Human Condition Through Distortion — History of Art #9

Francis Bacon, born in 1909, was one of the most influential and distinctive painters of the 20th century. He was renowned for his ability to depict the human figure in a disturbing and emotionally intense manner, often revealing deep psychological tension in his works.

The main themes in his work were the human condition, suffering, and isolation. Bacon's paintings are distinguished by their dramatic expression and somber atmosphere, filled with ambiguous emotions.

He created figurative paintings, strongly distorting the depicted figures, often placing them in interiors or against neutral backgrounds, sometimes additionally surrounding them with geometric cage-like structures.

The British artist of Irish origin turned away from the era's dominant abstract trends, instead developing a unique and unsettling form of realism. However, his works show the influences of cubism and expressionism.

His distorted human forms and vivid imagery incorporated elements of Expressionism, while his fragmented compositions and multiple perspectives echoed Cubist techniques.

Some classify him as part of the neo-figurative movement, however, it seems that Bacon created his own style, which was characterized by its unsettling realism and raw emotional power that was simultaneously modern and deeply emotional.

"If you want to convey fact, this can only ever be done through a form of distortion. You must distort to transform what is called appearance into image."

Two distinctive features that characterize Bacon's work are deformation and isolation. In his paintings, Bacon deliberately distorts human figures, twisting and stretching bodies to reveal deeper emotional and psychological truths.

This deformation goes beyond mere shock value; it's a means of penetrating the surface to expose the raw human condition.

Complementing this, Bacon often places his subjects within transparent geometric structures, creating a sense of isolation. These 'geometrical cages' serve to both confine and highlight the figures, emphasizing their vulnerability and alienation in the modern world.

Through these twin techniques of deformation and isolation, Bacon transforms ordinary appearances into powerful, evocative images that challenge viewers' perceptions and emotions.

Bacon's work represents a significant milestone in 20th-century art history. His artistic output is characterized by several distinctive features: the use of distortion, exploration of death-related themes, inspiration drawn from religious imagery, depiction of figures in isolation, and a fascination with the human body, particularly in its attempt to capture form in motion.

These elements create a unique artistic vision that continues to captivate and challenge viewers, solidifying Bacon's position as one of the most intriguing and influential painters of the 20th century.

1. Distortion

“I think there’s a whole area of forms which are organic. A form that relates to human image but is a complete distortion of it“

Although Francis Bacon never formally studied painting and was self-taught, he created his first paintings in 1929, at the age of 20.

During his travels to London, Paris, and Berlin, Bacon immersed himself in the art world, visiting numerous museums and galleries. These experiences exposed him to a wide array of artistic styles and techniques, but it was a particular exhibition that would prove transformative.

In Paris, Bacon encountered Pablo Picasso's work at Paul Rosenberg's gallery, an event that many believe sparked his decision to pursue painting seriously. Picasso's biomorphic forms and distorted figures, which seemed to blur the line between human and animal, left a lasting impression on the young artist.

This influence is evident in Bacon's early works, most notably in his breakthrough piece "Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion" (1944).

Photo by Giles Watson, available on Flickr under CC BY-SA 2.0, depicting 'Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion' (1944) by Francis Bacon.

"Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion" (1944) marked a pivotal moment in Bacon's career, introducing key elements that would define his future work. This triptych showcases distorted, agonized figures set against a stark orange background.

Bacon claimed these figures were inspired by the Furies of Greek mythology, yet their forms are barely recognizable as such. Instead, they embody raw emotion and visceral physicality.

The central panel is particularly striking, featuring a creature with an open, screaming mouth - a motif inspired by Sergei Eisenstein's film "The Battleship Potemkin". This haunting image of the screaming mouth would become a recurring theme in Bacon's work, symbolizing the primal cry of human anguish.

While the painting's title references the Crucifixion, Bacon's approach is deeply rooted in the horrors of the 20th century, particularly World War II. By focusing on the base of the Crucifixion and presenting distorted, suffering figures, Bacon shifts the viewer's attention from the divine to the earthly realm of human pain. In his interpretation, there is no dignity in suffering - a raw reflection of the millions who died in modern brutalities.

Bacon answers the question "Is it God or man who suffers on the cross?" by clearly choosing human suffering. His distorted figures are a powerful reminder of how cruel people can be to each other.

This secular, humanist approach allows Bacon to use the Crucifixion as a powerful metaphor for the human condition in the wake of unprecedented violence and suffering. By stripping away religious connotations, he creates a more immediate and visceral portrayal of human anguish that resonates with the collective trauma of his time.

The expression contained in Bacon's distortion became a defining characteristic of his work. He returned to the crucifixion theme several times, notably in his triptychs "Three Studies for a Crucifixion" (1962) and "Crucifixion" (1965), consistently placing the figures against intensely red or red-orange backgrounds. Years later, Bacon acknowledged that this subject served as an excellent starting point, well-established by old masters, from which he could begin exploring various areas of human behavior.

Francis Bacon, Three Studies for a Crucifixion, 1962. Guggenheim Museum in New York

Francis Bacon’s unique way of painting faces might have been shaped by more than just artistic style. Studies suggest his intense distortions and color shifts, often showing dark or grayish areas on the right side of faces, may reflect his own visual experiences. Combined with Bacon’s lifelong asthma, which affected his perception, these features give insight into how his personal perspective on human form could have influenced his famous style.

It’s worth adding that Bacon's work is deeply rooted in existentialism philosophy. This connection seems particularly fitting given that he shared his name with the famous English philosopher Francis Bacon, though their approaches to understanding human nature differed drastically. While the philosopher sought rational explanations, the artist explored the raw, emotional aspects of human existence.

His approach to distortion is particularly evident in his treatment of the human form. Bacon often depicted human skin in a way that evoked flayed animal carcasses hanging in butcher shop windows. This visceral representation of the human body emphasizes the raw, vulnerable nature of existence. The figures in his paintings appear distorted, caught in powerful motion, as if trapped in a whirlwind or storm. This sense of dynamic distortion adds to the emotional impact of his work, suggesting the turbulent nature of human experience.

The expression contained in Bacon's distortion and neo-figuration represents a unique dialogue between classical art and modern horror. While traditional painters sought to idealize the human form, Bacon deliberately shattered these conventions by transforming his subjects into raw, writhing entities that seem to emerge from the depths of nightmare.

His figures aren't simply distorted; they appear to be caught in the process of transformation, like butterflies struggling to emerge from their chrysalis, except here the metamorphosis is reversed - the beautiful breaks down into the grotesque. This tension between classical composition and violent distortion creates a powerful commentary on the facade of civilization, suggesting that beneath our carefully constructed social masks lies a more primitive, visceral truth about human nature.

This tension is powerfully exemplified in Bacon's "Oedipus and the Sphinx after Ingres" (1983), where he dramatically reinterprets Ingres' neoclassical masterpiece. The traditional myth becomes a scene of visceral confrontation, with the sphinx transformed into a distorted nude figure and Oedipus rendered as a twisted form with bandaged, bleeding feet. Against a striking pink background, Bacon retains the basic compositional elements of Ingres' work but strips away its classical refinement. Through his characteristic distortion, the mythological narrative becomes a raw portrayal of human vulnerability and violence.

Francis Bacon, Oedipus and the Sphinx After Ingres, 1983. Source: Filip Pręgowski, (original title: Francis Bacon. Metamorfozy obrazu), DiG Publishing House, Warsaw 2011, CC BY 3.0.

Francis Bacon’s graphic works reflect his relentless strive to “open the valves of feeling.” He acted as a self-proclaimed witness of mankind, setting himself the task of scrutinizing the human condition. Whether self-portraits, depictions of former lovers, or evocations of the human figure, each produces the same expressive and fiercely charged effect seen in his paintings. He worked closely with his printmakers to capture the same color quality, especially evident in the bright pinks and deep blacks.

Bacon's use of distortion serves as more than just a stylistic choice - it becomes a powerful tool for expressing the human condition in all its complexity. Through his distorted figures, he creates a visual language that speaks directly to the viewer's unconscious, bypassing rational thought to reach something more primal and truthful about human existence.

His work suggests that to understand humanity fully, we must look beyond the surface to the twisted, distorted reality that lies beneath our carefully constructed appearances. The distortion in his paintings serves as windows into this deeper truth, revealing the vulnerability, pain, and raw emotion that define the human experience.

2) Isolation

“I think that the moment a number of figures become involved, you immediately come onto the story-telling aspect of the relationships between figures. And that immediately sets up a kind of narrative. I always hope to be able to make a great number of figures without a narrative.”

What is truly captivating about Bacon's paintings is the sense of isolation in the composition of his work. The figures he painted often exist in utter solitude, surrounded by circles, rings, or separated by lines, almost as if they are caged. They inhabit a realm of their own, a space that is inaccessible to the viewer. It’s as if they linger on the edge of non-existence.

A recurring theme in Bacon's work is the portrayal of figures enclosed or trapped within confined spaces. This motif of isolation is central to his artistic vision, reflecting the existential solitude of the human experience. By placing his subjects in these claustrophobic settings, Bacon evokes a profound sense of alienation that resonates with the viewer's own feelings of isolation in the modern world.

Bacon’s use of isolation isn’t merely a visual technique; it’s a psychological one. The boundaries he draws around his figures emphasize their detachment, trapping them in moments of anguish or contemplation. This creates a distance between the subject and the viewer, making the figures seem unreachable, even alien. It’s a reminder of the vulnerability and loneliness that can exist within the human experience.

These interior spaces serve as a dramatic backdrop for Bacon's distorted figures, amplifying the psychological tension and emotional turmoil present in his art. The stark contrast between the restricted environment and the dynamic, often contorted forms within it heightens the sense of inner struggle and outer confinement that characterizes much of Bacon's oeuvre.

Moreover, the use of these enclosed spaces invites viewers to engage in a deeper contemplation of the human condition. The figures appear to be caught in a relentless struggle against their surroundings, symbolizing the universal quest for freedom and connection.

This tension between the desire for liberation and the reality of confinement creates a haunting atmosphere that lingers long after viewing, prompting reflection on the nature of existence and the often isolating experience of being human.

In Bacon's world, isolation becomes not just a physical state but a profound commentary on the emotional barriers that can separate us from one another.

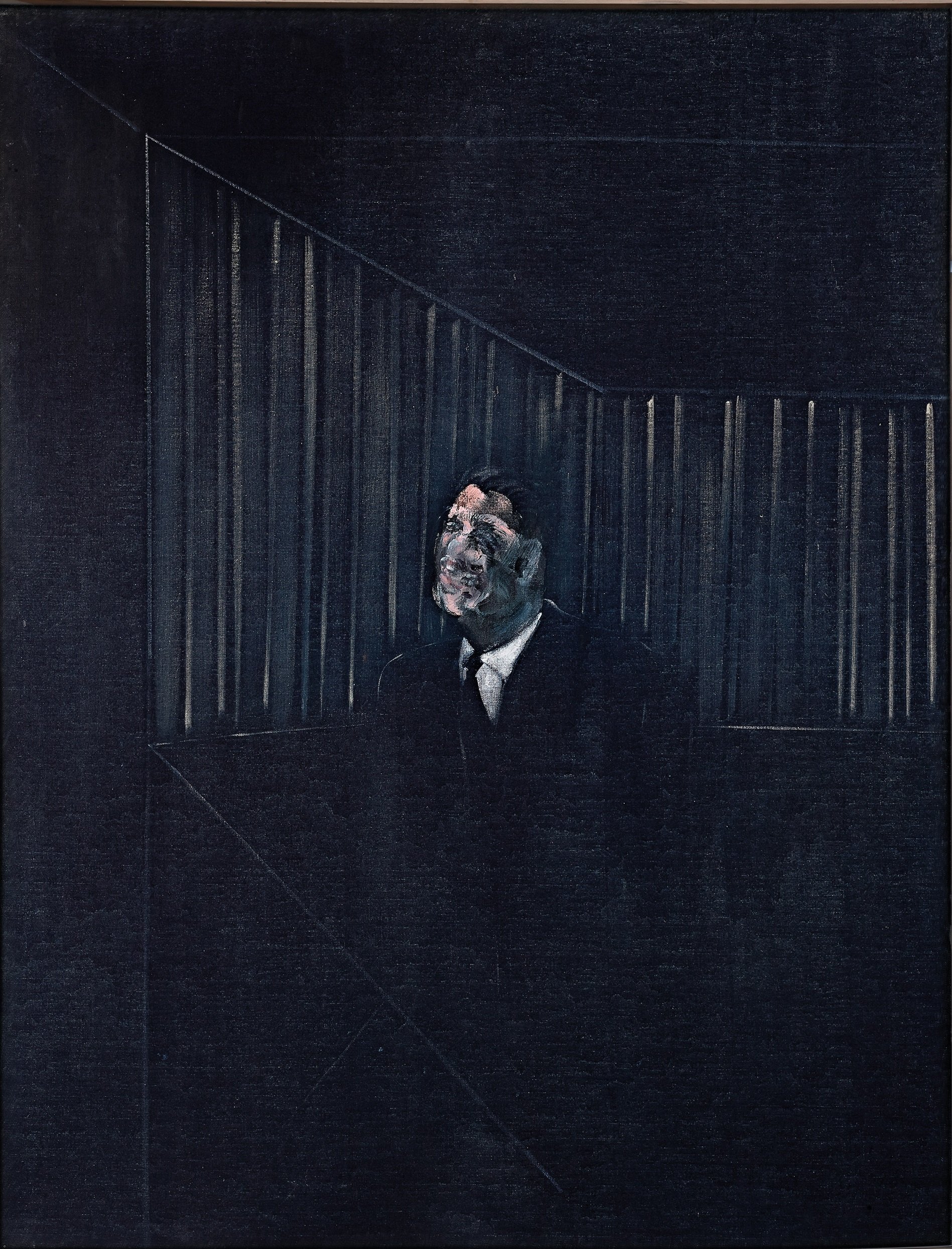

A perfect embodiment of this concept can be found in Bacon's "Study for a Portrait" (1952), where the artist masterfully demonstrates his technical and psychological approach to isolation.

Francis Bacon, Study for a Portrait, 1952. Tate Britain, London,

In this haunting portrait, the figure appears trapped mid-scream within a geometric, cage-like structure that both frames and confines him. Simple yet precise lines form a translucent box, creating a barrier between the subject and the viewer and intensifying the feeling of psychological separation.

The figure’s placement within this confined space is especially impactful—the transparent cube seems to weigh down on the screaming man, while a horizontal blue band in the background compresses the scene, adding to the claustrophobic effect.

Bacon’s use of these spatial constraints deepens the emotional intensity of the work, illustrating how he harnessed restricted space to heighten psychological tension.

The distorted expression of the subject, combined with the rigid geometric frame around him, powerfully conveys a sense of inner anguish, as if raw emotion is forcibly contained within an external boundary.

"Most of those pictures were done of somebody who was always in a state of unease, while working on all sorts of very private feelings about behavior and about the way life is.

Portrait of George Dyer in the Mirror by Francis Bacon, 1968, via Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved.

In “Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror”, Francis Bacon captures his lover, George Dyer, caught in a haunting scene of introspection. Dyer is shown seated, seemingly gazing into a mirror, yet his reflection is grotesquely distorted, amplifying the sense of psychological isolation. The composition creates a powerful feeling of seclusion; the empty, undefined space around Dyer suggests a void, emphasizing his emotional detachment and existential loneliness.

Bacon's use of space heightens this isolation. The background is stark and almost featureless, blurring the boundaries between the figure and the surrounding emptiness. This ambiguity of setting, combined with the harsh spotlight on Dyer, makes it seem as if he’s suspended in an emotional limbo—a solitary figure caught between the physical world and a metaphysical abyss.

In Bacon’s work, isolation often manifests through visual elements like empty backgrounds or the use of frames and cages, symbolizing barriers between the subjects and the outside world. Here, Dyer appears enclosed within his own mind, separated not by literal lines, but by the intangible cage of his reflection and the surrounding void. Bacon's style reflects his view of human isolation as something profound, a feeling of being trapped within oneself, both exposed and unreachable.

Isolation in Bacon’s work reveals his profound exploration of the human condition. His paintings often depict figures in states of anguish or vulnerability, capturing the pain of existing in a world where true connection feels out of reach. The cages and barriers that enclose his figures symbolize more than just physical confinement; they represent the emotional and psychological walls that isolate people from each other and from their own inner selves.

Through these visual barriers, Bacon speaks to a universal experience of existential isolation—an intense solitude that resonates deeply, exposing the fragility of the human spirit.

In this way, his art not only reflects individual suffering but also invites viewers to confront the loneliness embedded within the human experience.

3) Rawness

"My painting is not violent; it's life that is violent."

The rawness in Francis Bacon's painting is far more than an aesthetic technique—it is a fundamental existential experience. His work represents a systematic stripping away of the human condition from layers of convention, illusions, and cultural masks. Bacon does not paint violence; he reveals its persistent, silent existence within life itself.

His paintings are an intimate geography of human suffering, where flesh becomes a landscape of raw, primal emotions. Each brushstroke uncovers what lies hidden beneath layers of cultural correctness—the naked, painful, often shameful dimensions of human experience.

Photo by Uri Jimenez Carrasco, available on Flickr under CC BY 2.0, depicting 'Figure with Meat' (1954) by Francis Bacon.

One of the most powerful manifestations of this rawness appears in Bacon's Figure with Meat. This haunting work presents a distorted papal figure seated between two hanging carcasses, creating a visceral dialogue between power and vulnerability. The painting deliberately subverts Diego Velázquez's dignified Portrait of Pope Innocent X, transforming the image of ecclesiastical authority into a screaming figure stripped of all pretense. The pope's anguished expression and distorted features suggest a profound unmasking of human vulnerability.

The hanging meat carcasses that frame the figure serve multiple purposes. They remind us of our own mortality and corporeal nature, while simultaneously blurring the distinction between human and animal flesh. This juxtaposition of sacred and profane—a religious figure surrounded by butchered meat—creates a powerful commentary on the human condition. The raw meat, painted with Bacon's characteristic brutal honesty, emphasizes our shared physical vulnerability, regardless of social status or authority.

What makes Bacon's approach particularly innovative is his ability to merge the human and the animalistic, creating a visceral reminder that beneath our cultured exterior lies the same raw, vulnerable substance that comprises all living things. Through this unflinching portrayal of flesh—both human and animal—Bacon forces viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about their own mortality and physical nature.

The artist's fascination with raw meat and animal carcasses appears repeatedly throughout his work, serving as a reminder of our own materiality. In paintings such as "Fragment of a Crucifixion," or "Carcass of Meat and Bird of Prey", suspended meat becomes both a backdrop and metaphor for human vulnerability.

These recurring motifs of flesh and meat emphasize the visceral quality of existence that Bacon sought to capture in his work.

Francis Bacon, Fragment of Crucifixion, 1950. Source: twitter

Bacon's Fragment of a Crucifixion (1950) stands as one of his most visceral explorations of raw existence. The painting presents a brutal scene: two animal-like figures locked in a primal struggle of life and death. The upper creature, resembling both a dog and a cat, crouches over its prey on a T-shaped structure, while blood pours from its mouth. Below, the victim—a hybrid creature with both owl and human features—writhes in its final moments.

The rawness of the scene is emphasized through several artistic choices. The canvas is deliberately stripped of color, rendered primarily in stark whites and blacks against an unfinished background. This minimal palette forces viewers to confront the pure physicality of the struggle, unmitigated by any aesthetic softening. The streams of red paint, representing blood, cut through this monochromatic scheme with shocking directness, emphasizing the visceral nature of the encounter.

What makes this work particularly unsettling is Bacon's fusion of human and animal elements. The lower figure's distinctly human mouth and anatomical features create an uncomfortable bridge between animal violence and human suffering. This deliberate blurring of boundaries strips away the comfortable distinction between human and beast, suggesting that at our most fundamental level, we share the same raw, primitive nature.

The painting's religious title serves not as a promise of redemption but rather as a stark reminder of the brutality inherent in existence. The T-shaped structure, suggesting Christ's cross, becomes merely a stage for primal violence. Small, indifferent figures sketched in the background further emphasize the painting's bleakness—they pass by, oblivious to the raw drama unfolding before them, suggesting humanity's inability or unwillingness to confront its own savage nature.

Through this unflinching portrayal of violence and suffering, Fragment of a Crucifixion embodies the essence of rawness in Bacon's work. It presents life stripped of all pretense, revealing the brutal, primitive forces that lie beneath the surface of civilized existence. The unfinished quality of the canvas itself, with large areas left bare, mirrors this act of stripping away, suggesting that truth lies not in completion or refinement, but in the raw, unadorned reality of existence.

Francis Bacon, Carcass of Meat and Bird of Prey, 1980

Here, in "Carcass of Meat and Bird of Prey" (1980), Bacon confronts us with existence in its rawest form.

The suspended meat, vulnerable yet powerful in its brutal display, together with the predatory bird, strips away all civilized pretense. Through this stark arrangement of flesh and predator, Bacon forces us to face the unfiltered truth about our own nature - one that we often try to hide beneath layers of sophistication, but which remains fundamentally raw and primal at its core.

In exploring rawness, Bacon strips away the comfortable illusions that shield us from life's brutal realities. Through his distinctive visual language of distorted figures, exposed flesh, and unsettling juxtapositions, he reveals the profound vulnerability that lies at the heart of human existence.

His work challenges viewers to confront these uncomfortable truths, suggesting that authentic human experience can only be found by acknowledging our raw, unvarnished nature.

4) Bacon's Portrait Painting

Francis Bacon's portraiture was deeply personal, often focusing on his closest relationships. His subjects included intimate friends and lovers who were more than mere models: Isabel Rawsthorne and Henrietta Moraes, both close friends and muses; Lucian Freud, a fellow painter and lifelong friend; and his romantic partners Peter Lacy and George Dyer.

Among these, George Dyer held a particularly significant place. A young man from London's notorious East End with a background in petty crime, Dyer allegedly entered Bacon's life by breaking into his studio through a window. Their relationship transcended conventional boundaries, combining an erotic fascination with a complex, almost paternal form of love.

In Bacon's artistic universe, portraits were never mere representations, but psychological excavations. Each subject became a landscape of human fragility, where external appearances dissolved to reveal inner turmoil. His portraits functioned like emotional X-rays, stripping away social facades to expose the trembling essence of individual experience.

“I want to paint like Velázquez but with the texture of a hippopotamus skin. I would like my picture to look as if a human being had passed between them, like a snail, leaving a trail of the human presence and memory of the past events as a snail leaves its slime.”

For Bacon, a portrait was more than a visual likeness; it was a residue of human experience. The human figure in his paintings becomes a landscape of past events, with each distortion representing the traces of lived moments. His portraits leave behind an indelible mark of human vulnerability, transforming traditional portraiture into a visceral exploration of existence.

Francis Bacon, Head III, 1949

At the end of the 1940s, Bacon created his landmark Head series, a collection of provocative portraits that radically deconstructed human representation. These paintings presented anonymous, almost spectral figures, reduced to essential fragments - often identifiable only by the stark outline of open mouths and teeth. Rendered primarily in monochromatic grays and blacks, the works were characterized by trembling, vertical brushstrokes that seemed to vibrate with psychological tension.

More than mere visual experiments, these paintings represented a profound exploration of human perception. Bacon's brushwork suggested the fragmented nature of visual experience - not as a smooth, continuous image, but as a series of rapid, incomplete neural snapshots. The deliberate distortion of form mirrored the brain's complex process of constructing reality: an imperfect, constantly shifting interpretation of visual information.

By fragmenting facial features and challenging traditional portraiture, Bacon transformed these works into powerful meditations on identity, perception, and the unstable boundaries of human consciousness.

One of the most significant inspirations for Francis Bacon's work was a striking still image from Sergei Eisenstein's 1925 silent film Battleship Potemkin. Bacon frequently cited this haunting scene, which captures a woman's anguished scream after witnessing a tragic death, as a key catalyst for his own artistic pursuits.

Still from Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin (1925) showing nurse’s scream. source: wikipedia.org, CC BY 3.0

The expressive, fragmented portrait of the human face at the edge of legibility left a deep impression on Bacon, influencing his own explorations in portraiture. Inspired by the raw visual power of the Potemkin still, Bacon sought to create equally moving, though often unsettling, depictions of the human condition through his distinctive style of distorting and deconstructing facial features.

In the late 1940s, Bacon became captivated by Velazquez's painting Portrait of Pope Innocent X. This fascination lasted for many years, with Bacon producing his own interpretations of the work up until the 1970s. When asked about the reason for his interest, Bacon responded:

"I've always thought that this was one of the greatest paintings in the world and I've had a crush on it. Velázquez was in some ways the most miraculous painter, and he was able to come so near to almost, you could say, illustration, yet with strange and subtle deformations turn these very human and personal things into great images."

Bacon admired how Velazquez was able to so precisely capture the deepest and most profound human emotions in his painting. The Spanish master's ability to represent these very personal elements, while also introducing subtle distortions, was something that greatly inspired Bacon in his own exploration of portraiture.

Interestingly, despite having the opportunity to view Velazquez's original painting in Rome, Bacon never dared to do so. He instead relied solely on reproductions, amassing a large collection of books containing these reproductions, as he feared being confronted by the reality of Velazquez's work after his own manipulations of the image.

Bacon was concerned that if he were to see the original painting, he would be preoccupied with the "stupid things" he had done to it in his own interpretations.

Diego Velázquez, Portrait of Innocent X, 1650. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

In his interpretations of Velazquez's famous Portrait of Pope Innocent X, Bacon often made radical transformations to the original image. Instead of the dignified, composed face of the Pope, Bacon typically replaced it with a cynical, contorted expression. In many of his versions, the figure of Innocent X appears to be screaming - sometimes in terror, at other times in anger and fury.

'Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X' (1953) by Francis Bacon, photo by Libby Rosof, available on Flickr under CC BY 2.0.

Bacon also drew inspiration from another renowned work - the expressionistic still from Eisenstein's film Battleship Potemkin. In several of his interpretations of the papal portrait, the artist superimposed the curved glasses and widely opened mouth taken directly from the terrified woman in that cinematic frame onto Innocent X's face.

Francis Bacon, Study for a Head,1952. Photograph: Sotheby’s

Furthermore, Bacon created versions that placed the seated figure of the Pope against a backdrop of two hanging carcasses of beef. This grotesque juxtaposition heightened the ominous, macabre tone of the entire image, introducing associations with the large, animal-like wings behind the man. Bacon even posed for photographs himself alongside these split beef carcasses, reflecting this distinctive compositional element.

Created in the immediate aftermath of World War II, Bacon's "Painting" is an oblique but damning image of an anonymous public figure. The umbrella and dark suit evoke specific political associations, while the deathly complexion and toothy grimace suggest deep brutality beneath the proper exterior. The glaring colors and cruciform arrangement of cow carcasses in the background further accentuate the sense of menace, drawing from Bacon's childhood fascination with butcher shops as well as classical artistic treatments of the subject.

Through these radical deformations and unsettling juxtapositions, Bacon sought to extract a deeper expression of the human condition, far exceeding the calm, classical portrayal of his Old Master influences.

Portrait painting was at the core of Bacon's artistic practice, serving as a vehicle for his profound explorations of the human condition. Rather than striving for classical realism, Bacon radically deconstructed and distorted the human figure, reflecting his belief that identity was not a fixed construct but a fragile, ever-shifting process.

Through his radical deconstruction of the portrait, Bacon sought to transcend mere visual likeness, striving instead to capture the primal, unstable essence of human identity. His portrait paintings became a means of grappling with the fragmented, elusive nature of the self, reflecting his belief that the truths of the psyche lay not in outward appearances, but in the realm of the subconscious.

5) Influence of Photography

“I have always been very interested in photography. I have looked at far more photographs than I have paintings. Because their reality is stronger than reality itself.”

Bacon's subjects often appear captured in unconventional, seemingly casual moments - sprawled, sleeping with bent legs, or seated in relaxed, intimate positions that suggest an unguarded glimpse of human existence. In works like "Three Studies of Lucian Freud" (1969) and "Triptych - Two Figures Lying on a Bed with Attendants" (1968), his figures exude an extraordinary sense of unposed authenticity.

Francis Bacon, Two Figures Lying on a Bed with Attendants, 1968. Source: Filip Pręgowski, (original title: Francis Bacon. Metamorfozy obrazu), DiG Publishing House, Warsaw 2011, CC BY 3.0.

This remarkable effect stemmed from Bacon's unique approach: he rarely painted from live models, instead working from photographic images captured by close friends and photographers like John Deakin, Peter Beard, and John Edwards. Deakin's photographs particularly fascinated Bacon - quickly shot without elaborate staging or carefully arranged lighting. Bacon saw himself more as a documentarian of everyday moments than a traditional artist, and his paintings reflect this documentary-like quality.

The concept of photography as a tool for dissecting movement and perception resonates deeply with Bacon's artistic vision. Stop-motion photography - a technique developed in the 19th century to capture movements too rapid or too slow for human perception - mirrors Bacon's own artistic method of fragmenting and reconstructing human form. Just as stop-motion animation assembles minimally different images to create the illusion of movement, Bacon assembled visual fragments to create a more intense, layered representation of the human experience.

This approach aligned perfectly with Bacon's philosophical understanding of visual perception. As he noted:

"When you witness an event, you are often incapable of explaining it in detail... Whereas when you look at an image symbolising the event, you can pause over the event as it happened and feel it more strongly."

Photography offered him a means to deconstruct and reimagine human movement, emotion, and existence.

It's worth noting two distinct types of photography that profoundly influenced Bacon's artistic vision. While portrait photography shaped his approach to capturing human figures, both medical documentation and press photography played equally significant roles in developing his unique visual language.

Medical photography, including X-rays and clinical images, revealed Bacon's fascination with the body's interior landscapes. These unflinching documentations of human anatomy aligned with his quest to expose what lies beneath surface appearances.

Similarly, press photography, especially images of conflict and violence, provided raw material that Bacon transformed through his distinct painterly vision, inspiring the screaming figures and distorted bodies that became hallmarks of his work.

In discussing Bacon's relationship with photography, it's worth noting how his earlier works, like "Figure with Meat" (1954), showing Pope Innocent X seated between two hanging carcasses, find their echo in photographs of the artist himself.

A striking example is John Deakin's 1952 photograph for VOGUE, where Bacon poses shirtless against a backdrop of bisected animal carcasses, creating a haunting parallel to his painted works.

John Deacon, Photography of Francis Bacon for VOGUE, 1952.

Such imagery underlines Bacon's exploration of the human body in its most exposed and vulnerable form, using meat as a symbol of mortality and the visceral nature of existence.

Photographs like this one may have served as visual references or simply resonated with Bacon's thematic focus, reinforcing his interest in the brutal realities of flesh, which became central to his distinctive and haunting style.

Photography had a profound impact on Francis Bacon's artistic vision, shaping both his methods and his approach to capturing the human condition. Using photographs not for strict realism but as starting points for distortion, Bacon was particularly drawn to images that conveyed rawness and vulnerability. His fascination with motion studies, portraits, and medical photographs provided him with perspectives that he would transform on canvas to heighten emotional intensity.

Photography served as a foundation from which Bacon could abstract and push boundaries, creating works that feel both grounded in reality and hauntingly surreal, ultimately helping him probe the darker truths of human existence.

6) Existentialism and the Human Condition

“The greatest art always returns you to the vulnerability of the human situation.“

Francis Bacon’s art immerses us in a world of existential struggle and raw exposure. His paintings do not simply depict figures; they lay bare the human condition in all its fragility and brutality.

Although Bacon never explicitly engaged with existentialism, there is a striking common ground between his work and existentialist themes. His paintings evoke a visceral, immediate experience—a confrontation with life’s inherent uncertainties and the fundamental vulnerability that shapes our existence.

In Bacon’s world, life unfolds in a space devoid of inherent meaning, and each person must carve out their own identity amidst uncertainty. Existentialist thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre emphasized the importance of self-determination, claiming that individuals must “create” themselves without relying on fate, societal expectations, or pre-existing narratives.

Bacon captures this unsettling freedom through figures that appear both physically and emotionally isolated, seemingly suspended in an endless journey of self-definition. They are trapped within the confines of their own experience, mirroring the existentialist belief that we are ultimately alone in our inner worlds.

Albert Camus’s concept of the absurd—that life is inherently meaningless and our search for purpose is often futile—is echoed in Bacon’s depiction of deformed, distorted figures. Bacon’s subjects do not embody heroic ideals or clear narratives; rather, they are fragile, sometimes grotesque forms, presented without any attempt to beautify or idealize.

Just as Camus insisted on accepting the absurdity of life without illusion, Bacon presents life in its most unfiltered, brutal reality. His art offers no solace or escape; it merely presents the human condition as it is—a state fraught with suffering, uncertainty, and the constant, often frustrating, search for meaning.

In the context of existentialism, it’s worth mentioning Triptych, May–June 1973 by Francis Bacon, a work that powerfully illustrates themes of grief, mortality, and the fragility of human existence. Painted shortly after the death of his lover, George Dyer, this triptych captures not only Bacon’s personal loss but also existentialist ideas about isolation, despair, and the inevitability of death.

Through haunting, distorted figures set in claustrophobic, confined spaces, Bacon challenges viewers to confront the raw realities of human vulnerability and the limitations of connection.

Francis Bacon, Triptych May-June, 1973. Oil on canvas, 198 × 147 cm. Collection of Esther Grether. Source: tate.org.uk

The triptych’s three panels each show Dyer’s form in various states of physical and emotional collapse, presented within cage-like frames that intensify the sense of confinement. The left panel shows Dyer hunched over in a desolate bathroom, a figure contorted and blurred, evoking physical and psychological dissolution.

In the central panel, Dyer’s shadowy form leans forward under a single lightbulb, surrounded by darkness, suggesting isolation and the weight of despair. The right panel shows Dyer slumped, disappearing into a shadowy void—a powerful symbol of mortality and the erasure of self.

This triptych resonates with existentialist themes by portraying life as a fragile, solitary struggle in the face of inevitable death. The distorted and decaying forms capture the vulnerability of the human body and the isolation that defines our existence.

Like existentialist philosophy, Bacon’s work offers no comfort or clear answers; instead, it confronts us with the inescapable realities of suffering and loss, leaving us to grapple with the weight of our own mortality.

Created in 1954, Bacon's "Man in Blue" series epitomizes his existentialist vision of human vulnerability and isolation. Through a sequence of paintings depicting anonymous figures in business attire, confined within shadowy, cage-like spaces, Bacon explores the fundamental solitude that Sartre and Camus identified as central to human existence.

These works, with their vertical bars and somber palette, are a manifestation of existential crisis, presenting figures trapped in the absurdity of modern life, stripped of pretense and exposed in their fundamental isolation.

Similar to other works from the Man in Blue series, Man in Blue VII provides a powerful articulation of existential isolation.

The solitary figure emerges from the darkness, his face distorted and twisted against a backdrop of imprisoning vertical bars. Clad in a conventional suit—a symbol of societal order and conformity—this figure’s deformed features sharply contrast with his formal attire. This tension between outward appearance and inner turmoil resonates with existentialist ideas, suggesting that we are ultimately isolated in our inner worlds, trapped within the confines of our own experiences.

The predominantly blue-black palette and confined space intensify the painting's existential weight, while the figure's distorted features suggest the raw vulnerability that Bacon considered central to the human condition. Like Sartre's conception of a man condemned to be free, the figure appears suspended in a void of meaning, facing existence's fundamental uncertainties.

Through this haunting image, Bacon captures not just isolation, but the essential existential struggle of maintaining authenticity in a world devoid of inherent meaning.

While Bacon was not directly associated with existentialism, his art naturally aligns with existentialist themes through its raw depiction of human vulnerability and isolation. His distorted figures and confined spaces create a visual language that powerfully expresses existential concerns about the human condition.

Through his unique artistic vision, Bacon becomes a kind of visual existentialist, confronting viewers with profound questions about isolation, authenticity, and the fundamental struggles of human existence.

Summary

Francis Bacon's works possess an extraordinary power to shock, disturb, and leave an indelible mark on the viewer's consciousness. Interestingly, the British artist was sometimes accused of subjecting his audience to visual violence. His response to these accusations was particularly revealing:

“I’m always surprised when people speak of violence in my work. I don’t find it at all violent myself. I don’t know why people think it is. I never look for violence. There is an element of realism in my pictures which might perhaps give that impression, but life is violent, so much more violent than anything I can do!“

Bacon's art offers a hauntingly raw exploration of human existence, drawing viewers into intense emotional landscapes shaped by deformation, isolation, and existential dread.

His paintings, characterized by distorted bodies and confined spaces, penetrate beyond surface appearances to uncover the darker, often concealed aspects of the human condition. Through his visceral and unsettling style, Bacon exposed the vulnerabilities, fears, and primal emotions that many would prefer to ignore.

If you found this article intriguing or are interested in collaborating, feel free to connect with me on Twitter or visit my personal website.