Exploring Futurism: Art Movement Embracing Modernity, Dynamism, and Rejecting Tradition — History of Art #3

Futurism became a unique Italian contribution to the European artistic revolution unfolding at the turn of the 20th century. The name symbolized both a program and a battle cry. Ambitions were high: Italy aimed to liberate itself from rigid traditions and assume spiritual leadership in Europe. The founder, leader, organizer, and patron of this politico-literary-artistic movement was Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who brought futurism to life in the autumn of 1908.

It's worth mentioning that Marinetti was by no means an unknown figure. Whether in the editorial sanctums of literary journals, on lecture platforms, or in salons across France and Italy, he moved with effortless familiarity.

His literature, especially his poems, was saturated with dynamic energy, reflecting the desire for modernity and the future. Marinetti experimented with form, using free verse to break free from traditional structures and emphasize the innovative character of the futurist movement. This freedom of form allowed him to express emotion, movement, and modernity in a way that wasn't constrained by conventions. In this way, his literature became a manifesto for the dynamic artistic revolution characterizing futurism.

Italian Futurists, Luigi Russolo, Carlo Carrà, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini, 1912 via Wikimedia commons, Public domain

First Futurist Manifesto, 1909

“We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath...a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.”

In 1909, the Parisian newspaper Le Figaro published the First Futurist Manifesto by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, aiming to transform the face of art and make it as modern as the rapidly advancing world at the dawn of the 20th century.

Marinetti and the artists surrounding him rejected conventions and anything tied to tradition. They were fascinated by technological inventions and the societal changes linked to the progressing industrial revolution and urban development. They viewed libraries and museums as examples of archaic culture that impeded creative growth. Additionally, it's worth noting that simultaneously, Dadaism was evolving — a movement that shared many similar principles.

The manner of representation was changing, and there was a growing need for uninhibited creative expression. In essence, it was a period of literary and artistic experimentation.

1. We want to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and rashness.

2. The essential elements of our poetry will be courage, audacity and revolt.

3. Literature has up to now magnified pensive immobility, ecstasy and slumber. We want to exalt movements of aggression, feverish sleeplessness, the double march, the perilous leap, the slap and the blow with the fist.

4. We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath ... a roaring motor car which seems to run on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

5. We want to sing the man at the wheel, the ideal axis of which crosses the earth, itself hurled along its orbit.

6. The poet must spend himself with warmth, glamour and prodigality to increase the enthusiastic fervor of the primordial elements.

7. Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Poetry must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.

8. We are on the extreme promontory of the centuries! What is the use of looking behind at the moment when we must open the mysterious shutters of the impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We are already living in the absolute, since we have already created eternal, omnipresent speed.

9. We want to glorify war - the only cure for the world - militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman.

10. We want to demolish museums and libraries, fight morality, feminism and all opportunist and utilitarian cowardice.

11. We will sing of the great crowds agitated by work, pleasure and revolt; the multi-colored and polyphonic surf of revolutions in modern capitals: the nocturnal vibration of the arsenals and the workshops beneath their violent electric moons: the gluttonous railway stations devouring smoking serpents; factories suspended from the clouds by the thread of their smoke; bridges with the leap of gymnasts flung across the diabolic cutlery of sunny rivers: adventurous steamers sniffing the horizon; great-breasted locomotives, puffing on the rails like enormous steel horses with long tubes for bridle, and the gliding flight of aeroplanes whose propeller sounds like the flapping of a flag and the applause of enthusiastic crowds.

The Futurists were inclined to believe that the manifesto struck out of the blue, catapulting the Futurism movement to global fame overnight. However, in reality, they made numerous attempts to gain the attention of literary figures for the new movement, and not all reactions were entirely positive.

The Futurists proclaimed pride, energy, militarism, and national expansion, considering opportunism, pacifism, and sentimentalism as disgraceful. They wanted young people to despise imitation and pedantry. Futurists aimed for the youth to have a passion for free and uninhibited inspiration, rebel against excessive sentimentality, and be fascinated and accustomed to danger.

The founder of the Futurist movement wanted young artists to follow their instincts, containing vast life forces that must be free and fully developed. Marinetti argued that a young poet's creative spirit is killed by confronting them with the old poems of a deceased poet from half a century ago. Publishers throw manuscripts of a starving genius into the trash, wasting money on publishing works from bygone eras.

Marinetti organized poetry evenings where he clarified the essence of "futurism." He explicitly states that futurism embodies a hatred for the past, and the movement's goal is to fight against the cult of the past.

Ideological Foundations

Before delving into the definition of futurist art, it is essential to establish the context and ideological foundations behind Futurism. Despite their differences, they shared a common ground – an unwavering love for Italy, placing this sentiment above all, even freedom.

Additionally, Marinetti declared that in Futurism, everything is permitted, except opposition to Italy. The intellectual and artistic primacy of Italy was an undisputed fact for the Futurists, requiring no justification.

According to the Futurists, Italians were the most artistically gifted nation, possessing a "sense of universality." For them, this great Italy had one formidable enemy - the Vatican.

While it may seem paradoxical in a nation with such a robust Catholic tradition, the Church itself was considered the primary adversary; futurist artists did not tolerate compromises, including matters related to the clergy. They didn't settle for merely advocating a clear separation between the state and the church; rather, they aimed for the complete elimination of the Vatican.

Futurists lamented that schools were filled with Christian morality, which they believed mandated unreasonable forgiveness, leading to what they considered systematic cowardice. They insisted that schools should accustom children to danger through sports and trials of courage.

They didn't want the church to be a 'monopolizer of human ideals,' so the clergy should stay away from the educational environment, all in order for Italy to stand as a great, industrialized, and militarily powerful nation.

It's also worth noting that in 1913, the Futurists formulated their political program. However, they took a decidedly negative stance towards both political parties and the parliament formed as a result of free elections.

Marinetti proposed the transformation of the parliament through the equal participation of industrialists, workers, and engineers in governing the country. The number of lawyers and professor representatives should be minimized, as he deemed the former opportunistic and the latter backward.

If, however, such a form of government did not prove effective, Marinetti then proposed creating a government composed of 20 experts elected through a popular vote, without the establishment of a parliament.

It is also worth mentioning that the 19th and 20th centuries were a time when Italy was a kingdom; therefore, Marinetti put forth his demands to the monarch:

1. The Italian monarchy, preparing for war, must above all foster a sense of national pride.

2. He must withdraw from the Triple Alliance, which the Futurists saw as a shameful alliance, as it was associated with Austria — a foreign imperial power that was opposed to the unification of Italy. Additionally, Austria, with its traditions and feudal structures, was seen as an obstacle to modernization and progress.

3. He must crush the worst internal enemy — clericalism, and he must liberate the Italian capital from the Vatican.

4. He must rebuild Rome as an industrial and commercial power and, at the same time, free Italy from humiliating and capricious dependence on foreign industry.

The main goal that guided Marinetti was to create a state led by experts and governed by artists. He attributed the terrifying state of corruption, opportunism, and skepticism to politicians.

Futurists proclaimed pride, energy, and national expansion. They praised patriotism and militarism, and what many did not like—they extolled war as the hygiene of the world. They called upon young talents from Italy to fight against people who were opportunists or ally themselves with the clergy.

They disagreed with all forms of opportunism, considering the axiom "in medio stat virtus" (virtue stands in the middle) as idiotic. They held in contempt and fought against any form of obedience, submission, and imitation. They reject the cozy lifestyle and we glorify nomads, praise the unruly, and celebrate wildness.

Context Behind Futurist Art

Futurist art originated from a transfer of a specific worldview onto the domains of literature, painting, sculpture, architecture, and music. In this art form, creative intuition was meant to replace logical approaches, improvisation to supersede learned rules, and a return to nature was intended to signify a replacement of culture. For the Futurists, the purpose of art was to depict life, and as they understood life as movement, dynamism, and ubiquitous speed that transcends the categories of space and time. Futurist art was meant to express this dynamic energy.

Marinetti's foreign travels and his encounters with literary and artistic circles facilitated the popularization of Futurism in Europe. Numerous painting exhibitions provided opportunities for French, English, and German creators to acquaint themselves with new ideas.

Interestingly, the Futurists, despite proclaiming their demands, did not actively seek public approval. They held the belief that gaining acceptance through concessions to common taste was beneath them, and they solely aimed to please their ideals.

Since 1910, the Futurists were very active, entering an intensive period of literary and artistic experiments.

Futurist Literature

“There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Poetry must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man“

Futurist literature, led by its founder Marinetti, plays a crucial role in the futurism movement. It served as a starting point for exploring other fields of art and laid the foundation upon which these fields were built.

Marinetti's literature, particularly his poems, pulsated with dynamic energy, embodying a longing for modernity and the future. Marinetti experimented with form, employing free verse (verso libero) to liberate himself from traditional structures and underscore the innovative spirit of the futurist movement. This flexibility in form allowed him to articulate dynamism and modernity without the constraints of conventions. In this manner, his literature became a manifesto for a dynamic artistic revolution, defining futurism.

The main principles of the new literary school of the Futurists were proclaimed in the Italian magazine "Poesia," founded by Marinetti in Milan in 1905. These principles were inspired by an intense desire for fight and renewal at any cost, arising from a sense of saturation and disenchantment with the past.

The Futurists described contemporary literature as a slave to the past, succumbing to an overwhelming number of unbearable conventions and traditions, blind to the passion of young artists.

Over time, Marinetti declared that regular free verse became outdated, and in its place, he advocated for ‘liberated words’ known also as ‘words in freedom’ (parole in libertà). Marinetti claimed that the purpose of free verse (verso libero) was to liberate poetry from traditional constraints, such as established metrical and rhyming patterns. However, aiming to further liberate language, he introduced the concept of "parole in libertà," which was intended to emancipate language from the old syntax, sometimes reaching even back to the era of Homer.

Marinetti additionally proclaimed that nouns should be arbitrarily combined, verbs used only in the infinitive, and punctuation replaced with mathematical symbols. The goal was to create a telegraphic style relying on mental associations. For example, the sentence "Mariah is similar to a dancer" could be replaced with "Mariah — dancer." And the description of war can be condensed into a simple equation based on associations: “Battle = guns + soldiers“.

Marinetti's "Words in Freedom" meant poetic expression based on the complete autonomy of individual words, free from traditional and logical syntax.

Additionally, Marinetti aimed to eliminate first-person forms, like "I". As a result, the futuristic language ceased to be a logical sequence of thoughts, transforming instead into a sequence of emotions and images. Furthermore, onomatopoeia began to play a significant role, for instance, serving to mimic the sounds of exploding grenades or the roar of an engine.

Filippo tommaso marinetti, parole in libertà via Wikimedia commons, Public domain

This new syntax proposed by Marinetti was meant to be accompanied by a novel printing method, characterized by the utilization of diverse fonts and varied spacing. The goal was to highlight, through the visual presentation of the text, the significance of individual words or entire sets of words.

In the realm of literary content, they advocate for scientific literature, which should be free from classical tendencies while celebrating the latest discoveries and dynamism of modern society.

Additionally, they aimed to abolish sentimentalism and romanticism, which they labeled as the "tyranny of love," in favor of militancy and dynamism. For this reason, the true literary hero for the Futurists ceased to be Don Juan and became Napoleon, known for his courage and immense reserves of strength, enabling him to conduct prolonged wars.

Futurist Painting

The main goal of Futurist painting was not to rebel against social order but to express the fundamental principle of life through new artistic means, reflecting the dynamic changes in society, technology, and culture. For them, this main principle was speed, dynamism, or, in psychological terms, "élan vital" — a concept formulated by the French philosopher Henri Bergson, representing an elusive source of life force and creative energy, giving reality an unpredictable and dynamic character.

The Futurists considered artistic means inherited from culture as worn out and unsuitable for conveying the emotions experienced by society, completely transformed by scientific advancements and engineering achievements. The new living conditions introduced numerous elements of nature that were entirely novel and had not found a place in art.

And for these elements, Futurists wanted to create new means of expression at all costs. Through innovative techniques and experimenting with form, shape, and surface, the Futurists aimed to portray a dynamic reality full of the symphony of motion.

Umberto Boccioni, The City Rises, 1910 via Wikimedia commons, Public domain

The Futurists, eager to spread their ideas throughout Europe, organized numerous events to promote their movement. The posters inviting people to the Futurist party at Teatro Lirico, created by two young artists, Umberto Boccioni and Luigi Russolo, gained them recognition.

These two artists were part of a circle of young talents shaping the new generation, influenced by Jugendstil, the Vienna Secession, and, most notably, the highly esteemed Gustav Klimt and Edvard Munch, whose lithographs from 1909 to 1910 left an impact on the young painters.

It's important to note that this group of new artists enthusiastically read Nietzsche, Bergson, Marx, and Engels, which also influenced them, especially in the context of overthrowing the existing order and creating a new quality.

The Futurists proclaimed numerous manifestos covering various art forms. In the early 1910s, a manifesto of Futurist painters was published in the form of a brochure. The authors were Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla, and Gino Severini.

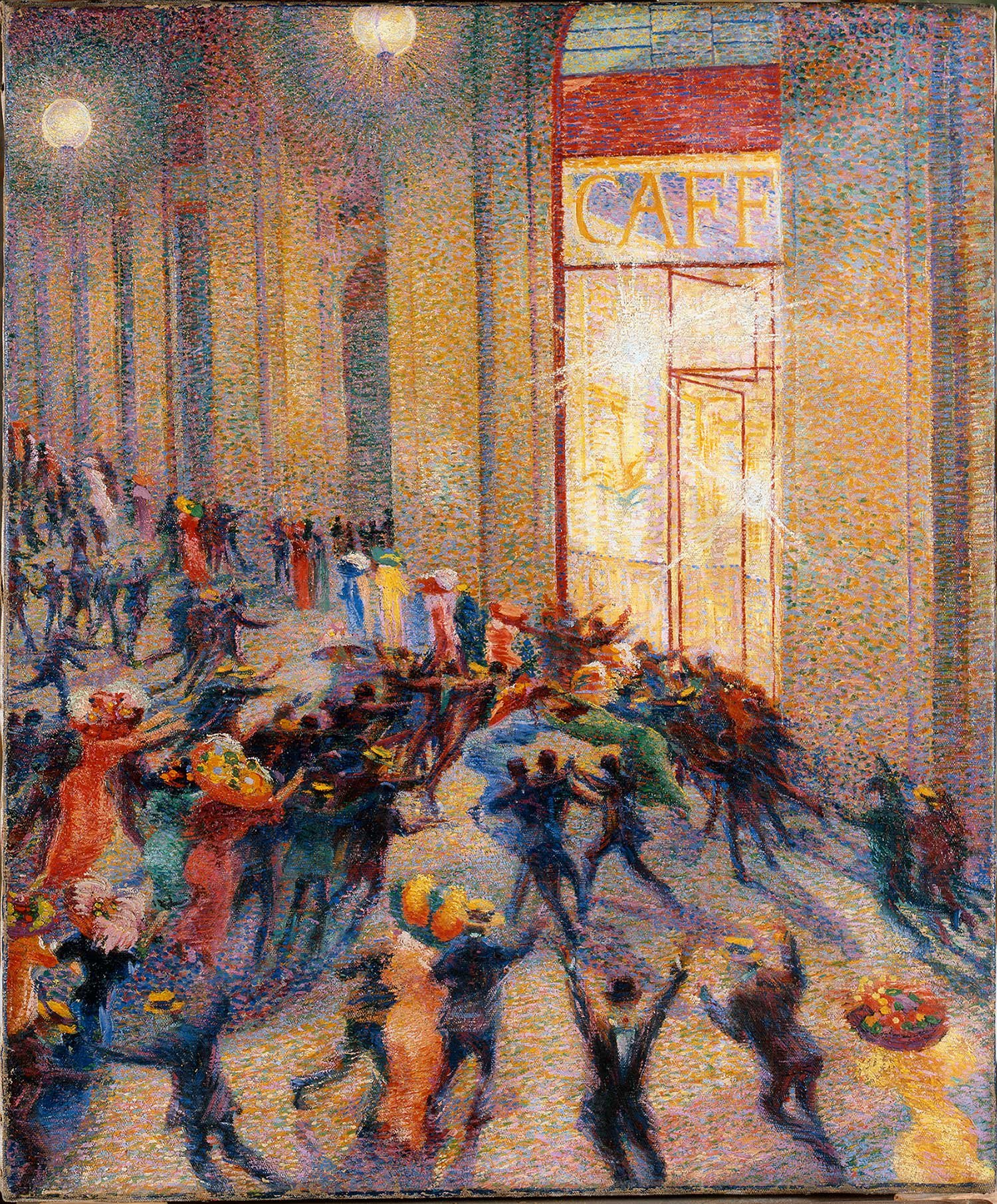

Umberto Boccioni, Riot in the Gallery, 1910 via Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

1. Destroy the cult of the past, the obsession with the ancients, pedantry and academic formalism.

2. Totally invalidate all kinds of imitation.

3. Elevate all attempts at originality, however daring, however violent.

4. Bear bravely and proudly the smear of ‘madness’ with which they try to gag all innovators.

5. Regard art critics as useless and dangerous.

6. Rebel against the tyranny of words: ‘Harmony’ and ‘good taste’ and other loose expressions which can be used to destroy the works of Rembrandt, Goya, Rodin…

7. Sweep the whole field of art clean of all themes and subjects which have been used in the past.

8. Support and glory in our day-to-day world, a world which is going to be continually and splendidly transformed by victorious Science.

The denial of tradition and the cult of the past expressed in the painters' manifesto from 1910 were still quite general. Drawing on the foundational manifesto from 1909, the painters provided some guidance on the new themes for paintings, proposing depictions of trains, steamships, airplanes, submarines, and the life of large cities. However, when it came to the question of 'how' these themes should be presented, it offered only one answer: originally.

Aroldo Bonzagni, The Tram in Monza, 1910-1915. Photo: Sailko via Wikimedia commons, CC BY 3.0

It's worth mentioning that from the beginning of the Futurist movement, they didn't have clearly defined methods of creation, and the confrontation with the European avant-garde compelled the Futurists to more precisely define their position.

The increase in knowledge, however, did not lead to a break with the previous period but to the consistent development of the proclaimed ideas since 1909. This maturation accelerated due to the encounter with new artistic currents from France, Germany, and Russia, particularly with the Cubists.

The first visible consequence of this process was a determined primacy of form. For the Futurists, it became clear that merely praising modern life or capturing it on canvas was not sufficient.

In April 1910, another manifesto of painters was published — Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto. The main ideas of the technical manifesto emphasize that the goal of painting is not to create a photographic reproduction of the external world but simply to reveal the principle of life. This principle of life is primarily universal dynamism, which painting should convey in the form of a dynamic experience.

Additionally, the encounter with the Parisian avant-garde, especially the Cubists, caused the issue of form, which had often taken a back seat to new themes during the year and a half of Futurist painting's existence, gaining priority.

Therefore, Futurists no longer reproduce nature and life through copying or improvising optical illusions; instead, they convey their emotions and dreams, highlighting them in harmonious forms and colors. They stated that light and motion annihilate the materiality of bodies, which are not closed-off objects but rather their form and color shape themselves under the influence of the environment.

With the concept of 'congenital complementarism,' the Futurists emphasized the artist's role in feeling life firsthand to shape it later. Furthermore, the artist compelled the viewer to experience the creative process, fostering active participation in the artwork.

Boccioni proposed a new type of painting that placed the viewer at its center, challenging the traditional stance of standing in front of the artwork. To achieve this, the painting had to be a synthesis of what one remembers and what one sees.

“In order to make the spectator live in the center of the picture, as we express it in our manifesto the picture must be the synthesis of what one remembers and what one sees.”

This concept is exemplified in Boccioni's theoretical framework and his series of three oil paintings known as "States of Mind"

Umberto Boccioni, States of Mind II: Those Who Go, 1911. Photo: Own work Selbymay via Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Boccioni sought a new approach to redefine the concept of a painting. Convinced that, after the exploration of light by the Impressionists, color by Cézanne, and form by Picasso and the Cubists, it was time to take a step further. Instead of focusing on compositional elements like color or form, he believed it was necessary to propose a new kind of comprehensive composition. Therefore, he proposed the painting of the invisible — that which cannot be visualized through conventional, traditional means.

In contrast to antiquity, the goals of Futurist painting were reversed. While the ancients contemplated conceptual abstractions and expressed them concretely, for instance, through sculptures reflecting the human body, the Futurists aimed to transform the concrete into abstractions through analysis, a concept referred to as the ‘state of mind’.

Futurist painters will no longer capture nature and humanity on canvas. Instead, they will elevate form to vibrations and speed, making it not an object but its rhythm — more precisely, the rhythm of an object in motion.

It is worth mentioning that the Impressionists, influenced by the advancements in contemporary science and photography, began to capture brief moments. In contrast, Futurists did not seek to convey purely optical impressions; instead, they aimed to express psychic experiences.

Umberto Bocionni, The Laugh, 1911 via Wikimedia commons, Public domain

For Boccioni, The ideal painter is one who, when seeking to depict a vision, such as a dream, does not paint a sleeping person but is capable of evoking the idea of the dream through lines and colors. Thus, the painter can bring forth the concept of a universal dream existing beyond the contingency of time and space.

“In painting a person on a balcony, seen from inside the room do not limit the scene to what the square of the window renders visible; we try to render the sum total of visual sensations which the person on the balcony has experienced”

The Futurists did not aspire to paint what we conventionally see—the content presented to us in the act of perceiving an object. Instead, their focus lay on the sensation evoked in us by this act of perception, even before crystallizing this feeling into a specific sense. In this pre-sensation, sensory perceptions and images of memory were intended to intermingle. They aimed to capture the pre-impression—the initial perception of the object before we comprehend what it is. By eliminating the categories of space and time, they sought to encapsulate emotions in a pure and universal form.

This synthesis of visual and mental elements leads to simultaneity, as the state of mind experiencing the object undergoes the elimination of both the passage of time and the distance of space. Boccioni referred to this intuitive contemplation, through which the artist reaches the essence of things, as "physical transcendentalism."

The first version of Boccioni's triptych, "States of Mind I: The Farewells," stands as a prime example of this type of painting.

Umberto Boccioni, States of Mind I: The Farewells, 1911 via Wikimedia commons, Public domain

The painter, capturing the moment of farewell at the train station, depicted it almost in ellipses, where the emotional scene of parting flows through diagonal lines. The color palette of the painting is dark and subdued, and in the central part of the first part of a triptych, attention is drawn to the departing train. The movement of the train indicates strong brushstrokes, influencing the shifting landscape.

Boccioni's experiments with form, the application of Cubist techniques, and his ability to grasp the dynamics of life moments, especially the farewell scene, make "The Farewell" an excellent illustration of how Futurists aimed to express not only static reality but also the emotions associated with life's moments. This significant work from the period aligns with the spirit of Futurist exploration of new means of expression. In this "States of Mind" painting, which was the last epigone of Symbolism, the influence of Munch can be noticed.

Influenced by Cubists, especially in terms of form in painting, the Futurists adopted many concepts from them and incorporated them into their own theories, such as breaking down objects or figures into elementary geometric forms. This geometrization became a tool for Futurist painters, enabling them to present a more convincing portrayal of the mutual interaction between the object and the environment.

Utilizing Cubist techniques, Boccioni breaks down forms into geometric elements and then combines them in a way that suggests movement and dynamism. Additionally, this technique gives the impression of planes interweaving, as the train is almost intertwined with its surrounding landscape.

In this way, States of Mind ceased to play the role of the work's theme; instead, it allowed the artist to express the dynamism manifested in the object, which is a part of the world. Thanks to this, a path to plastic dynamism opened up.

Desiring to depict the relationship between the subject and the object, the "States of Mind" paintings had to address a significant issue of plastic dynamism, concerning the connections of the object with its environment. According to Boccioni, the object is the essence of vibrations, manifested through colors, and simultaneously, an accumulation of directions that take the form of shapes in the phenomenon.

Futurists argued that there are no fixed and self-contained objects. Every living being, every object, is connected to its surroundings through lines of force — the subject influences the environment, and vice versa. When depicting an object, it is necessary to simultaneously showcase its relationships with the environment and reveal the atmosphere in which it exists. This is precisely where Futurists drew inspiration from Cézanne, aiming to establish the laws of mutual relations between objects and their surroundings.

Giacommo Balla, Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, 1912 via Wikimedia commons, Public domain

The goal of presenting an object and its surroundings within the scope of plastic dynamism began to gain greater significance, which was not so distinctly emphasized in the previous paintings.

In 1912, Giacomo Balla presented his inaugural Futurist paintings, including "Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash" and "The Hand of the Violinist (The Rhythms of the Bow)." Simultaneously, Boccioni showcased pieces like "Woman in a Café: Compenetrations of Lights and Planes." The titles themselves signify that the era of "States of Mind" had been surpassed. Dynamism, plane, form, and rhytm gained priority, becoming the crucial elements of Futurist painting.

Boccioni, drawing inspiration from Bergson, made a distinction between absolute and relative motion. Absolute motion is the inherent property of every body; its breath or heartbeat, which is also a part of the universal dynamism. Relative motion involves the displacement of a body from one point to another.

The result of simultaneous absolute and relative motion is a dynamic that gives rise to a new form (object + environment), corresponding to the continuous flow phase of life. This dynamic continuity represents a fundamental form captured through intuition and is further shaped by the movements of lines and colors, creating coherence.

A significant artistic element is the interpenetration of planes, where the environment (shape and color) actively participates in shaping the object, ultimately leading to a simultaneous view from different perspectives.

Umberto Boccioni, Simultaneous Visions, 1912 via Wikimedia commons, Public domain

In addition to the painting of "States of Mind" and plastic dynamism, Futurism also championed the painting of analogies, wherein objects were juxtaposed based on associations.

In Gino Severini's painting, "Dynamic Hieroglyphic of the Bal Tabarin," the entire scene of the ball and individual figures is not created from complete elements but is merely assembled based on associations. We see hats, dresses, fragments of faces, or decorations—and this is enough for us to create a complete image of the ball, using associations.

From this principle of associations, surrealism emerged, transferring associations into the realm of the unreal and destructive.

Givo Severini, Dynamic Hieroglyphic of the Bal Tabarin, 1912 via Wikipedia, Public domain

Umberto Boccioni, a young Italian artist, asserted that a day would come when a mere painting would no longer suffice. Its immobility amidst the ever-increasing movement of society would prove to be a comical anachronism. Furthermore, he stated that humans would reach a point where they perceive color as emotion, and replicating colors would no longer need forms to be perceived and understood. We would set aside canvases and brushes, and painting would evolve into an architectural work, integrating the viewer as a creator.

Futurist Sculpture

In 1912, Boccioni, the sole creator and theorist of Futurist sculpture, published the Sculpture Manifesto, in which he expressed opposition to classical art and the works of Michelangelo. In this manifesto, Boccioni also makes a couple of points that allow us to get the bigger picture of what he wanted to achieve:

1. The aim of sculpture is the abstract reconstruction of the planes and volumes which determine form, not their figurative value.

2. One must abolish in sculpture, as in all the arts, the traditionally “sublime” subject matter.

4. It is necessary to destroy the pretended nobility, entirely literary and traditional, of marble and bronze, and to deny squarely that one must use a single material for a sculptural ensemble. The sculptor can use twenty different materials, or even more, in a single work, provided that the plastic emotion requires it. Here is a modest sample of these materials: glass, wood, cardboard, cement, iron, horsehair, leather, cloth, mirrors, electric lights, etc.

8. There can be a reawakening only if we make a sculpture of milieu or environment, because only in this way can plasticity be developed, by being extended into space in order to model it. By means of the sculptor’s clay, the Futurist today can at last model the atmosphere which surrounds things.

10. One must destroy the systematic use of the nude and the traditional concept of the statue and the monument.

Futurist painting and its underlying concepts had a profound impact on various art forms. It is noteworthy that Futurist painters, who dedicated considerable attention to both the object and its surroundings, also left an indelible mark on sculpture. Futurist sculpture emerged by applying the formula originally designated for painting: object + environment.

However, a notable distinction between Boccioni's paintings and sculptures lies in the fact that, in paintings, the object and its surroundings underwent a holistic fusion and mutual interpenetration, whereas in sculpture, its constituent elements remained isolated.

Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913 via Wikimedia commons, CC0 1.0

Futurist sculpture, despite its isolated constituent elements, shared a common pursuit with Futurist painting in aspiring towards dynamism and the mutual interpenetration of forms. In open compositions, artists used the interaction of forces and combined different materials, treating form as a motion.

The most famous sculpture by Boccioni, currently housed in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, "Unique Forms of Continuity in Space," resembling a human figure, is, in reality, a spatial embodiment of movement. It embodies dynamism through the multiplication of vanishing and re-forming shapes. The moving sculpture refers to an endless motion, a continuous shifting of a smooth, gleaming form that is the quintessence of the force piercing through the air.

For Boccioni, what mattered was not pure form, but pure rhythm; not the construction of the body, but the construction of the action of that body. It's worth mentioning that the works of Rodin influenced the creativity of the Italian futurist. That's why the emptiness in Boccioni's sculptures is so emphasized—he aimed to achieve the goals of plastic dynamism and create a new form, penetrating the surroundings. Futurist sculpture was intended to animate the object and give the impression of its spatial continuation.

Additionally, he advocated for incorporating movable, mechanical elements into sculptures. Crucial for the further development of sculpture for Boccioni's was not to limit sculpture to just one material but to shape the sculpture from highly diverse materials, and even embed mechanical elements to set it in motion.

Boccioni is also the creator of many nonexistent sculptures that have been destroyed. For example, in the sculpture created in 1912, 'Head + House + Light,' Boccioni tackled the issue of the literal interpenetration of planes.

Umberto Boccioni, Head + House + Light, 1912, (destroyed) via Wikimedia commons, Public domain

Moreover, he advocated for employing polychromy in sculpture, emphasizing the importance of color in the mutual interpenetration of objects and their surroundings. In 1914, Boccioni created a work titled "Horse+Rider+Houses." The sculpture was made of wood and cardboard with the addition of copper and iron.

Boccioni pushed his ideas further, suggesting that to intensify emotions, one could use twenty different materials in a single piece, including glass, wood, texture, iron, and even horsehair.

Boccioni, like the rest of the Futurists, experimented with sculpture because they did not believe that an object ends where another begins. They asserted that the environment is crucial for sculpture since they interact with each other. In his pursuit of rejecting classical sculptural forms that had dominated European art for centuries, Boccioni decided to depict figures in an entirely new way, emphasizing the dynamism of movement and the space that surrounds it.

In sculpture, a medium traditionally considered static for centuries, Boccioni aimed to capture something elusive—the very movement itself, just as in painting, he sought to capture the invisible.

The goal of sculpture became the quest for the essence of motion and its existence in space.

Futurist Architecture

Futurist architecture, or more specifically, the architectural style pioneered by Antonio Sant'Elia, stands as Italy's sole contribution to modern architecture before World War I. The young architect from Como underwent formal education and was influenced by the same artistic currents as Boccioni, Carra, and Russolo, whom he was acquainted with long before he became involved in the Futurist movement. These influences encompassed figures such as Giuseppe Sommaruga and artists like Munch, Franz von Stuck, Gustav Klimt, and, more broadly, the Vienna Secession.

His projects, regrettably unrealized due to his premature death, showcased modern, dynamic forms, and concepts for cities of the future. The studies he included in his manifesto—Manifesto of Futurist Architecture 1914—are visual explorations. In this manifesto, Sant'Elia presented his vision of a modern city, known as "Città Nuova." Unfortunately, horizontal projections are lacking, and the concepts of transitioning from individual buildings to larger ensembles in the futuristic city are only lightly highlighted.

In line with futurist principles, Sant'Elia rejected eclecticism, as architects were not allowed to draw inspiration from objects of past centuries or photographs of oriental buildings. Instead, he believed that architects should treat the shape of a house or a planned city as an expression of contemporary society.

It is worth noting that Sant'Elia's designs distinctly distance themselves from the prominent buildings of European and American architects of the 20th century. The residential houses designed by the French architect Garnier in the "Cité Industrielle" project are surrounded by gardens and parks, whereas in a futuristic city, there is no room for trees and flowers; cement and metal dominate everywhere.

On the other hand, American architects like Wrich and Mies van der Rohe designed low, elongated buildings, while Sant'Elia envisioned massive blocks of houses with ten or more floors.

Sant'Elia, project of a skyscraper with external elevators and a three-level street, 1914 via Wikimedia commons, Public domain

His vision encompassed dynamic structures, skyscrapers, fast transportation, as well as the abandonment of stairs in favor of elevators, which, in addition, were externally positioned as a distinct architectural element in the design of the skyscraper in Città Nuova.

Sant'Elia dedicated significant attention to transportation issues, in line with the Futurist movement's focus on speed and modernity. The transportation system in his vision involved three distinct traffic zones—railways, cars, and pedestrian traffic—connected through the use of moving staircases and metal walkways. Additionally, he altered street levels or elevated building levels to ensure fast, collision-free communication with maximum safety assurance.

It's worth mentioning that in 1930, two Italian artists, Enrico Prampolini and Giuseppe Terragni, designed the Monument to the Fallen in Como, based on the Sant’Elia’s sketches from 1914.

Enrico Prampolini, Giuseppe Terragni, War Memorial (Monumento ai Caduti - Como), 1930. Photo: Marimari52 via Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

The visionary architect from Como, Antonio Sant'Elia, conceived a radical departure from traditional urban concepts, envisioning a city full of energy, movement, and modernity that would express the spirit of societal transformation.

His projects incorporated modern materials such as steel, concrete, and glass, which was unique in a time when traditional architectural forms dominated the urban landscape. He was a pioneer in utilizing materials and technologies that later became standard in modern architecture.

Antonio Sant'Elia, despite his brief tenure in the world of architecture, has left a legacy through revolutionary ideas and a visionary outlook on the future of architecture and urbanism. His works defined the foundations of the Futurism movement in architecture.

Futurist Theater

The Futurists, guided by the vision of creating art for contemporary society, largely rejected the relevance of traditional theater altogether, considering it completely outdated. They believed that its role should be taken over by "syntheses" reflecting modern life.

The Futurists envisioned a shift from a well-thought-out spectacle to a representation of life itself—hurried, chaotic, and dynamic.

In painting, the Futurists used the overlapping of planes as a visual technique. Similarly, in theater, elements of reality observed in a contemporary setting, like in a restaurant or on a tram, were intended to overlap.

Viewers stopped being passive observers and instead became active participants in the performances. The Futurists abandoned the opposition between the stage and the audience.

The futurist theater did not aim to evoke emotions or educate people; instead, it sought to delight them and, if possible, surprise them. The element of surprise was crucial for the Futurists.

Another demand of Futurist theater was, above all, the brevity and conciseness of the performance. Sketches often limited themselves to a few minutes. Interestingly, inanimate objects occasionally became the main characters of the action.

Additionally, it's worth mentioning that many Futurist painters, such as G. Balla and Prampolini, designed stage sets and costumes for performances.

Futurist Music

In futurist music, the same principles applied as in literature and painting, aiming to sever ties with tradition and establish connections with avant-garde movements. And just as onomatopoeia played a crucial role in literature by imitating the sounds of a revving engine, futurist music presented the noise of the modern city.

In 1906, the first quarter-tone composition was published, and in 1911, the composer Francesco Balilla Pratella, releasing the Technical Manifesto of Futurist Music, declared quarter-tone music a magnificent achievement of futurism.

Pratella intended to create absolute polyphony by merging harmonies and counterpoint into one. He was also convinced that it was essential to capture the musical "soul" of human masses, factories, trains, transatlantic liners, cruisers, cars, and airplanes.

In 1913, Luigi Russolo undertook a comparable initiative — exploring "noise music" (bruitism). He believed that for music to be relevant to modern life, it should incorporate noises, as the invention of machinery had given birth to a new realm of sound that now dominantly shapes our surroundings.

This noise music didn't have to limit itself to mere imitation but rather could organize noise material into harmonic and rhythmic structures. As it wasn't feasible with traditional musical instruments, Russolo constructed special intonarumori for six different noise groups, later codified into "The Art of Noises."

Although little of Russolo's music has survived, and his instruments were destroyed during the last war, these intonarumori, as primitive as they may have been, marked the beginning of electromechanical music.

Futurism — Worldview

1) Against Passeism:

The Futurists aspired to create a new, powerful, industrialized Italy, and to achieve this, they aimed to eradicate all remnants of the past—libraries, academies, and museums. They revolted against history, tradition, and everything associated with the past. They labeled all adversaries, including monarchs, the church, parliament, representatives of official art, and art critics, as "passeists." In essence, anything not aligned with Futurism was considered passeist.

They detested opportunism, pacifism, and sentimentality. Rejecting the past and the eternal yesterday, the Futurists advocated the cult of modernity, for which they coined the term "modernolatry." By this term, they meant the glorification of modern life in all its manifestations, with a special emphasis on the fascination with modern technology, especially means of communication—cars and airplanes. Speed, for Futurists, was the profoundest expression of modernity.

It is also worth adding that in 1903 the first Tour de France took place as well as the first flight of the Wright brothers, who rose into the air for a few seconds. In 1909, the first Giro d'Italia took place. Then came electricity, which not only revolutionized the lighting system, blurring the boundaries between day and night, but also endowed humanity with new inventions.

The Futurists tolerated neither mediocrity nor imitators. Art, for them, is only significant when it reflects modern life and envisions the future. Art cannot be indifferent to the achievements of the age of machines; it must pave the way towards the future.

2) Futurist hero

Many critics saw connections between Nietzsche and the Futurists. However, Marinetti vehemently denied this, as Nietzsche's Übermensch is born from the philosophical cult of Greek tragedy. Even though Nietzsche's Overman is oriented towards the future, it remains an apologist for the greatness of the ancient world, making it attached to the past.

Contrary to the Nietzschean ideal, the Futurists present their own ideal of man—the multiplied man, who promotes his strength, is an enemy of books, a student of machines, and a friend of his own experiences rather than ancient models. Additionally, he is equipped with wild instincts, cunning, and audacity.

Futurists desire a hero who is not inspired by antiquity and doesn't resurrect the ideals of the past, but creates what is new and has never existed before.

3) Living in danger

The Futurists claimed that only by engaging with danger and leading a daring and risky life, can a person fulfill themselves. That's why courage should be instilled in children at school and they should be encouraged to take bold actions, such as practicing sports.

Marinetti argued that sports not only toughen the body but also the mind, as they orient children towards competition and breaking records.

4) New Sensibility

Futurism involves a complete renewal of human sensibility, which is a consequence of great discoveries in the field of science.

Thanks to a twenty-four-hour train journey, every person can move from a small, lifeless town to a bustling metropolis full of light, movement, and noise. This new sensation of life, incorporating speed as an integral component, was not the result of logical thinking for the Futurists but was solely based on intuition. And this new intuition-based sensitivity should find its place in art.

Marinetti, in reference to the work of Henri Bergson, celebrated intuition as the decisive stimulus for the development of life and creative imagination.

5) Primitives of the 20th Century

Celebrating science and affirming mediumistic phenomena were by no means a deviation from nature for the Futurists.

Celebrating science and affirming mediumistic phenomena were by no means a deviation from nature for the Futurists. On the contrary, it was argued that thanks to science, humanity is brought back to a wonderful, higher, and primal barbarism that is not filled with tradition and culture; rather, it overcomes them.

Other artists in the 20th century sought primitiveness in the artistic expressions of primitive cultures, particularly in Central Africa. While the Futurists partially agreed with this, they believed it was too deeply rooted in the sphere of culture.

According to the Futurists, humans should express enthusiasm for modernity, which shapes the life of the 20th-century individual. This modernity, made possible by scientific inventions, encourages artists to experiment and improvise, which, according to the Futurists, represents true primitiveness.

6) Multiplicated Man

The future that was taking shape before the eyes of the 20th-century society demanded a new kind of human. The Futurists created, or more precisely, constructed this new human in the form of a multiplied man (uomo moltiplicato) with interchangeable parts, embodying a hybrid of a human and iron construction.

In this Multiplied man, moral pain, goodness, sympathy, and love are eliminated. He is constructed for omnipresent speed, bravery, and knowledge. According to the Futurists, such a multiplied man will become immune to love, which they deemed a disease, and will not experience old age because he will have replaceable prosthetics.

It's also worth adding for context that the achievements of medicine gave the impression that the vision of the Futurist man could become a reality. In 1902, the French physician Alexis Carrel invented a method for suturing blood vessels, making organ transplants in animals possible from 1908 onwards.

The multiplied man was virile, daring, and cruel. Moral goodness held no significance for him because everything that developed the physical, intellectual, and instinctual forces of humanity was considered good.

The highest value of the multiplied man is will, as only through will he can go beyond himself. The improvement and strengthening of the will became the main task of the futuristic man.

Summary:

Futurism, an early 20th-century avant-garde movement led by Filippo Marinetti, aimed to revolutionize Italian society by rejecting the past and embracing modernity. Futurists despised tradition, championing speed, technology, and danger as symbols of progress.

Their worldview sought a new, audacious hero—the multiplied man—devoid of sentimentality and inspired by machines. In art, literature, and music, Futurists celebrated intuition, sensorial renewal, and experimentation, rejecting established norms.

Antonio Sant'Elia extended these principles to architecture, envisioning a futuristic, industrialized city.

Futurism's impact reached diverse realms, influencing not only artistic expressions but also societal values and perceptions of the evolving 20th-century human experience.

If you find it interesting, get in touch with me on Twitter!