Exploring Pop Art: The Reflection of Popular Culture and Modern Society — History of Art #6

Photo: The MAC Belfast, available on Wikimedia Commons under CC BY-SA 3.0.

The best introduction to describing pop art, an art movement that emerged in the United Kingdom and the United States in the mid-1950s, would be to evoke the initial fragment of the manifesto written in 1961 by Claes Oldenburg, a Swedish-born American sculptor, and artist associated with pop art.

“I am for an art that is political-erotical-mystical, that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum.

I am for an art that grows up not knowing it is art at all, an art given the chance of having a staring point of zero.

I am for an art that embroils itself with the everyday crap & still comes out on top.

I am for an art that imitates the human, that is comic, if necessary, or violent, or whatever is necessary.

I am for an art that takes its form from the lines of life itself, that twists and extends and accumulates and spits and drips, and is heavy and coarse and blunt and sweet and stupid as life itself.

I am for an artist who vanishes, turning up in a white cap painting signs or hallways.

I am for an art that comes out of a chimney like black hair and scatters in the sky.

I am for an art that spills out of an old man's purse when he is bounced off a passing fender.

I am for the art out of a doggy's mouth, falling five stories from the roof.

I am for the art that a kid licks, after peeling away the wrapper.”

Much time has passed since the publication of Claes Oldenburg's declaration. Participants of the pop art movement have somewhat become classics. Gallery owners make huge fortunes on their paintings, just like collectors who are often also speculators.

In criticism, there are various opposing tendencies in the interpretation of pop art.

Some critics create an atmosphere of uncritical adoration around individual artists and their endeavors. Others, on the other hand, make generalizations, describing pop art as anti-intellectual or insensitive, yet it might seem that both sides too easily overlook what the most intelligent and creative participants of the discussed art movement have proposed.

We can say that when it comes to intelligence and artistic sensitivity, the situation looks similar to other art movements - some artists possess these qualities, while others do not.

However, while pop art deliberately depicted the full spectrum of social circumstances, which some argue may not favor intellectual effort and higher emotions among urban residents, it is essential to differentiate between the advantages and disadvantages of works classified as pop art and those of mass culture. And these distinctions have been interpreted differently within the realm of pop art.

The Context

Sociologists began writing about mass culture as early as the 1920s when new forms of entertainment, advertising techniques, and ways of spending leisure time emerged year after year.

American sociology, by its very nature, was the first to undertake the analysis of these previously unknown phenomena, which were rapidly growing in the United States society, generally dating back to the late 1930s.

Taking into account the profound influence of mass media and the pervasive impact of visual elements in the urban environment on the imagination, coupled with the insightful critiques from American scholars and journalists, it is indeed surprising that the artistic community reacted relatively late. It wasn't until the first half of the 1950s that they directly responded to the realities of everyday life. Furthermore, it's unexpected that it was the London artistic community, rather than the American one, that first responded to this phenomenon.

The acceleration of mass culture processes was avalanched thanks to the radio, millions of copies of pop music records, the indescribable boom in comics, the demand for useless gadgets, and the interest in mass organized tourism.

It's worth mentioning that pop art was not confined to mass culture, but primarily served as a commentary on the prevailing conditions of the fast-paced world of the 1950s. Additionally, the reception of pop art images was initially limited and did not, at the time, extend beyond the threshold of museum-like reception.

In the 1960s, despite the extensive media coverage Andy Warhol received and occasional attempts to imitate his style, his popularity paled compared to the immense popularity of music bands of that era, such as the Beatles.

Pop art is deeply intertwined with the conditions of social life, and although much is said about the plagiaristic stance of pop art artists, their role was not limited solely to indicating the iconography of mass media. It also encompassed the accurate and anticipatory portrayal of the fact that this iconography would become increasingly intense and aggressive.

The main idea of pop art was to explore the common themes found in modern society, spread through illustrations, posters, and prints. As a result, iconography in pop art circled back to its origins, revolutionizing and enhancing various fields of applied art, such as product packaging design.

This process intensified when the effects of unrealistic colors and linear drawings of human figures began to appear in mass-produced plastic bags, book covers, and above all, record covers designed by London pop art pioneers such as Richard Hamilton.

Pop art consciously and deliberately belonged to the ionosphere, to which man in the most industrialized countries belonged and which was so thoroughly described by sociologists in the 1950s.

In addition to the premeditation primarily characteristic of the participants of this movement in America, many artists also possessed a genuine sociological instinct. It is evident in the early theoretical interest in pop culture among a group of London artists associated with the Institute of Contemporary Art in the mid-1950s.

For instance, when James Rosenquist depicted exaggerated and infantile views of household appliances or gigantic faces with schematic, impersonal makeup, he did so in the context of the phenomena of homogenization in advertising and informational imagery. He thus mixed what was intended for overly adult children and infantilized adults. He did this within the framework of the same concept of homogenization described by sociologists such as Dwight Macdonald in his Theory of Mass Culture.

If, for example, Jim Dine or Öyvind Fahlström deliberately blurred the boundaries between painting technique and the symbolism of magazines, and rebuses, they also highlighted the same phenomena described by sociologists like Ernest van den Haag, author of the book "The Fabric of Society." van den Haag described how mass media, such as television, tend to transform art-related subjects into banal or trivialized entertainment themes.

Van den Haag described popular culture as something that coerces people into spending their leisure time on organized entertainment, something that's a ritual such as watching television, which according to him, systematically drowns out human despair and even kills individuality.

When Claes Oldenburg and James Rosenquist play with images of everyday groceries or household appliances, they, in their own way, illustrate the statement made by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in "Dialectic of Enlightenment" from 1947, describing the commodity as a fetish and advertising as an uncontrollable power.

So, when Richard Hamilton and Andy Warhol made their own image from someone else's photograph, it was because they aligned themselves with the "mechanical" image, which is objective and cold, yet susceptible to biased interpretations linked to the context of the photograph. Therefore, even though their photographic images appear to be innocent recordings of nature, they are sophisticated products of culture.

Pop art served to some extent to understand the functioning of mass imagery. In the case of pop art, art is not a monument of culture but rather a living and pulsating organism, reacting to dynamically changing social and cultural trends. Taking into consideration the time and place in which pop art emerged, including all the sociological phenomena occurring, pop art aimed to show that treating art as pure visualization, detached from other aspects of social life, is outdated and insufficient.

London and Popular Culture — Independent Group

London in the 1950s—there were no entertaining TV programs with The Beatles yet; instead, people went to see movies starring James Dean, who, like no other, foreshadowed the inevitable creation of a wall that would separate the older generation from the younger.

These changes, besides the James Dean films, were also discussed at the Institute of Contemporary Arts on Dover Street in London from 1952 to 1956, inspired by several painters, architects, and industrial designers united in the Independent Group.

The Independent Group's activities aimed to revive the artist as a universal figure in an increasingly complex and dynamic civilization. They also addressed other issues, such as forms of modern American culture like comics. Their discussions also focused on the aesthetics of a profit-oriented society

Although the Independent Group did not directly influence popular culture, they accurately described its impact and interpreted it insightfully.

The most deserving individual in the process of crystallizing new art in England was the painter and art theorist Richard Hamilton. Hamilton used the term "pop art" to describe the metropolitan landscape, from which the artist drew his own creative vision in the best sense of the word.

Thus, he treated all forms of "art," including advertisements, announcements, animated films, or passport photographs as material awaiting processing.

In the early fifties, he worked as a designer of everyday equipment, a painter, and a specialist in book design.

It seems that among all members of the Independent Group, he distinguished himself with the most intellectually motivated and radical views regarding new art; he was constantly searching for new means of expression.

He was an inspiration for many exhibitions, and he published theoretical studies. Richard Hamilton played a significant role in the conception and realization of the large collective exhibition This is Tomorrow in 1956 in London.

The exhibition showcased the "environment of man" — besides works of art, there were many elements of industrial design, graphic design, and modern equipment.

The thesis of the This is Tomorrow exhibition was the belief that art is not just a creation aimed at establishing a particular style, celebrated in art galleries, but an integral part of life.

Hamilton stated that his goal and desire were to expand our perceptual capabilities so that we could accept and utilize the constantly enriching visual material.

In 1957 Richard Hamilton defined pop art as follows:

“Pop Art is: popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous, and Big Business“

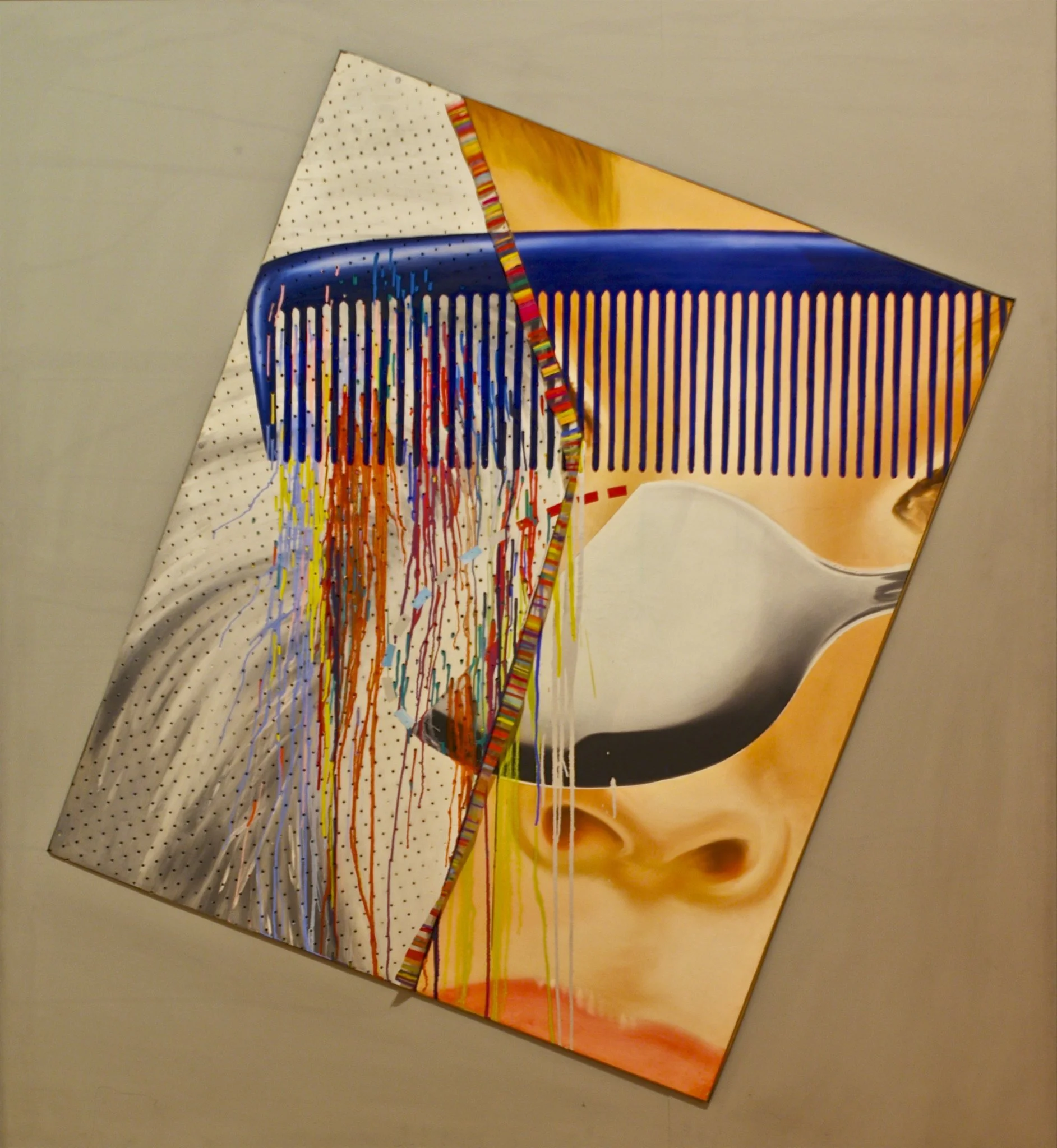

Hamilton's works thus became material for him, fulfilling the above conditions. They were works full of constant quotations and allusions, in which painted parts interacted with individual snippets from photographs, fragments of technical charts, quotations, and even pieces of clothing.

Analyzing Hamilton's works, one can conclude that each allusion was justified not in form or composition, but in the logic of vision, in a uniquely conceived sociology of modern society and culture.

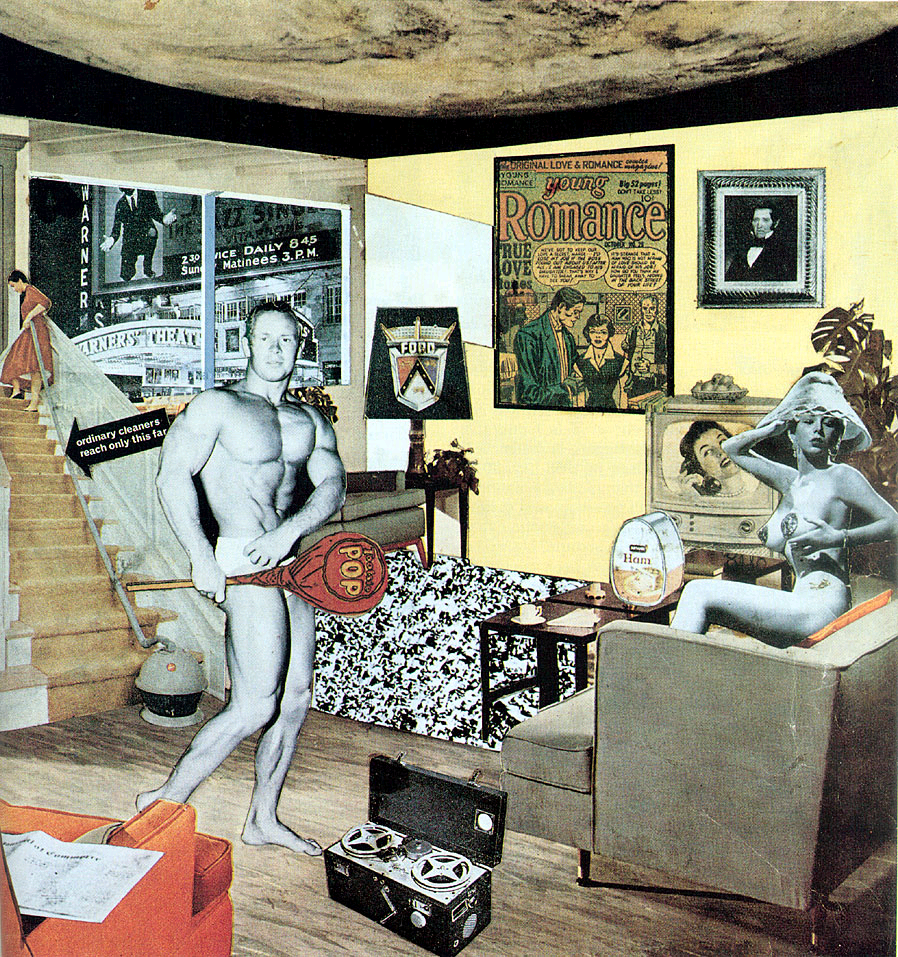

For example, his work "Just What is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, so Appealing?" is an ironic allusion to the catalogs of novelties advertised by department stores.

He used motifs captured from advertisements for household appliances, clothing, or cars, and all of this to hyperbolize the experience - in his works, aggressive things became even more aggressive, pleasant things became even more pleasant, and the artificiality of these things was openly artificial.

In all of his paintings, the aim was to depict literal slices of the world, to grapple with the filtering vision of the artist against reality. Relativism and skepticism towards the objective relationship from the confrontation with the world are characteristic features of Hamilton. He experimented with the interpretation and perception of reality, emphasizing the subjective nature of human perspective on the world.

The impression of his figment of the imagination even emanates from his paintings or screenprints, based on the most literal motives, such as a photographed scene from a newspaper depicting one of the members of the Rolling Stones and his companion, arrested in a drug scandal, or a freeze-frame from a television screen depicting the massacre of students by police in the USA.

The expression of these shots relies on nervous commentary, not just about the incidents themselves but about the messages conveyed to society by the mass media.

The self-thematization of Hamilton's paintings primarily involved transforming real motifs into a kind of phantasmagoria, serving as a physical reflection of a slice of the world. His works not only depicted selected fragments of reality but also raised questions about the nature of the image itself and its role as a medium of communication.

By employing techniques such as collage, serigraphy, and photo manipulation, Hamilton provoked viewers to reflect on how the media shape our perception of the world and how reality can be interpreted and transformed in the context of contemporary mass culture.

His works served as a sort of mirror of society, reflecting its images, dreams, and fears, while simultaneously compelling critical analysis of the relationship between perception and reality.

One of the leading London artists of the time was Eduardo Paolozzi, a Scottish artist who was able to utilize surrealism in a way that resonated with him — the belief that beyond "refined" art, there exist other realms rich in sources of inspiration.

He drew inspiration from the covers of crime novels and lottery tickets. Paolozzi also explored areas far removed from art, such as print retouching, tattooing, Mickey Mouse films, or anatomical atlases.

In the 1950s, Paolozzi had his own vision of civilization, which Marshall McLuhan dubbed the "Mechanical Bride", tempting with the promise of pleasures provided by the abundance of consumer goods and the accessibility of mass media.

The pioneering book by McLuhan from 1951, which described the influence of advertising on society and culture, was also the subject of discussions initiated by Paolozzi at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London.

Eduardo Paolozzi, God of the Forge, 1971. Photo: Set in Stone Project via Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Paolozzi, alongside Warhol, contributed to the trend of utilizing graphics where the artist intentionally limited their manual actions, focusing primarily on directing a specialized team of printers, programming the tonality and framing of the photographs and the color scheme.

It was an ostentatious declaration that artists align themselves with a world where mass media reigns supreme, where even the sound of a singer's voice on stage is technologically prepared, and where every poster is created in collaboration between the author and printing technology specialists.

Eduardo Paolozzi, Newton, 1995. Photo: Loco Steve via Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA 2.0

Paolozzi distinguished himself by greater sarcasm than other artists. His retrospective exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London in 1971 was decorated with multiple reproductions, slogans, boards, and a cast of a spatial boot, similar to those worn by American soldiers in Vietnam.

This boot was a symbol of aggression that served as a kind of memento. And its obsessive presence at the exhibition was a sign of solidarity with all those young Londoners who mocked the establishment.

As the world gained momentum, alongside insightful commentary on the modern world, London's music-fueled culture also produced many primitive, tacky, or kitschy works.

In the mid-1960s, only a few painters, such as Richard Hamilton, maintained independence and a critical sense, selecting themes convenient for themselves in the surrounding visual landscape using modern reproduction techniques.

They maintained this independence regardless of sporadically providing services, such as for the industry of record covers or stage set designs. These very painters created the most valuable assets, consciously attempting to establish a certain "meta-language" that commented on popular culture and modern society.

It was a confrontation between the language of art and the ever-changing nature of life.

Manhattan Artists

In the United States, the wave of pop art emerged in 1959, beginning with Allan Kaprow's happenings and Claes Oldenburg's exhibitions, until Andy Warhol's transition from a window decorator and advertising graphic artist to a painter. This process ultimately crystallized in 1962, when the term "pop art" was also used to describe the works of these artists.

From the beginning of the movement, alongside Lichtenstein and the even more famous Warhol, there were artists whose works cannot be unequivocally classified into the pop art iconography, such as George Segal, Edward Kienholz, or before-mentioned Claes Oldenburg.

George Segal, older than most artists of this milieu, portrayed characters in expansive interiors filled with furniture and tools, where one could say his characters vegetate. They are somewhat a cast of a person acting in everyday situations. His works celebrate mundanity, weariness, and simple human dignity.

Exhibition of George Segal’s works in 1965. Photo: F.N. Broers / Anefo via Wikimedia commons, CC0

George Segal is an artist who transcends various conventions and evokes the presence of another human being. Without comment, Segal describes what a gas station employee or a woman operating a laundry does.

Real objects create tension with the white plaster figures between the coldness of materials and the human spontaneity of fleeting gestures. Despite this structural diversity, the objects interact with the figures.

We can argue that this makes the author of The Gas Station a stranger to the extremely conventionalized iconography of pop art, which turns the human figure into an impersonal sign on par with any other inanimate symbol, deliberately avoiding individuality as seen in the works of Andy Warhol, for example.

It's also worth mentioning Edward Kienholz, an American installation artist and assemblage sculptor, who, although not associated with pop art, similarly to Segal, attempted to provide a thoughtful commentary on American reality.

His attempt was certainly utopian because the vision of the human condition cannot be captured even in the most multifaceted and illustrative environments, but was worth mentioning, especially for its difference from conventional pop art.

Edward Kienholz, The Beanery, 1965. Photo: Pemboid via Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Kienholz's work is closer to the activities of a wax figure cabinet than to classical, smoothed-out pop art. His function was also entirely different from conventional pop art, as he aimed to scream out disgust. With this very disgust, he arranged every piece of furniture in the interiors of shacks, middle-class bedrooms, taverns, or doctor's offices.

Although Kienholz's work was less expressive than Warhol's and did not fit into the frame of conventional pop art, it is worth mentioning him because he commented on reality as well differently. Additionally, he encountered a certain sensitivity among viewers, who found inspiration in his work "The Beanery".

In the beginning, we mentioned a fragment of Claes Oldenburg's manifesto, the Swedish-American sculptor who is considered one of the most creative figures in artistic circles associated with pop art.

His manifestos express a profound awareness of his artistic goals. They encompass a nuanced assessment of the contemporary society surrounding him — from glorification to irony, all the way to a pervasive indifference towards all aesthetic criteria and tastes (both good and bad).

His works, which include absurdly large cloth sculptures and painted models of everyday objects, produced between 1961 and 1964, are named after items found on the menus of budget self-service bars, fitting well within the conventions of pop art. However, he was searching for a different kind of expression.

His works are primarily a reconciliation of paradoxes and provocations, especially visible in his creations made of slippery and soft materials filled with porous sponges.

Paradox and provocation are particularly visible in titles themselves such as "Soft Scissors". Additionally, the materials used in his works are an invitation to touch these products and establish contact with them. It represents an unconventional form of expression that Claes Oldenburg aimed to achieve.

First of all, Oldenburg reconciles the contradictions between artificial systems - such as a series of plaster models or models of household appliances - which may seem schematic and boring, with human openness. Through each work - from sketches, through projects, to artistic events - he comments not only on reality but also on the relationship of art, sculpture, and events to this reality.

Oldenburg managed to touch upon certain conceptual issues that go beyond the trivial literalness of his works and even beyond the usual irony towards the materialistic attitude of consumer society. In his art, Oldenburg addressed philosophical and social issues, going beyond the mere form and superficiality of his works.

Claes Oldenburg uses everyday objects as the subjects of his works, and through unconventional representations, his pieces not only reflect reality but also alter it. It challenges the classical definition of a painting as a simple reflection of the surrounding world. He aims to reveal the emptiness in "still life" and figurative sculpture.

Through the humor embedded in forms hanging limply toward the ground, he exposes the falsity of frozen gestures in Baroque sculptures and the gigantism of 19th-century monuments.

Oldenburg's art demonstrates that our perception of reality can be ambiguous or false.

His art highlights the difficulty in defining the essence of objects and argues that reality is not easily definable; going further, it suggests the need to refute supposedly inherent characteristics of reality such as hardness or permanence. Similar to Duchamp, who disrupted our sense of reality by presenting marble cubes in the form of sugar cubes, leading everyone to believe that his work was light and sweet.

We can say that a humorous sense of utopia is a characteristic feature of Oldenburg's works.

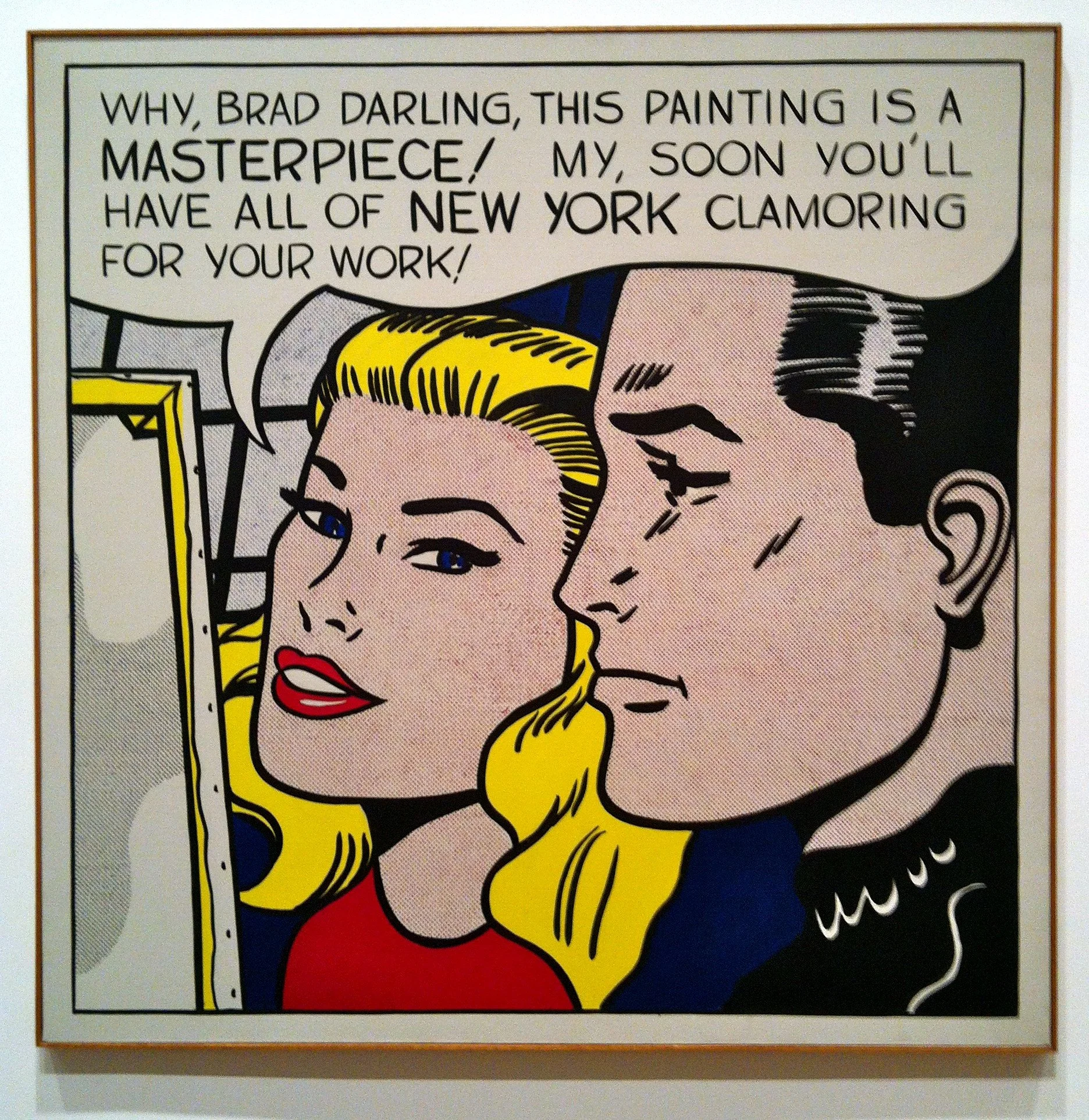

Another artist considered a typical representative of pop art is Roy Lichtenstein. His technique of overlaying images with a grid of dots, the schematic nature of iconography, and the placement of text in speech balloons make him the epitome of the entire conventionality and impersonality that characterize this art movement.

Despite all this conventionality, Lichtenstein wanted to set a challenge — proposing a certain commentary on painting and our viewing habits in general — he aimed to suggest and question certain types of expression and emotionality.

The expression of Lichtenstein's paintings is both loud and cold. It can be observed that the artist's involvement is inversely proportional to the subject of the painting.

It is evident in how emotions are portrayed in a piece where a girl has a broken heart and in another piece where jet fighters are battling.

Roy Lichtenstein, Kiss V, 1964. Photo: Myosotis alpestre via Wikimedia commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

Imitating the comic book style of the 1950s or employing superficial sentimentality borrowed from commercial graphics was Lichtenstein's ambition to create a paraphrase of numerous themes present in art and beyond.

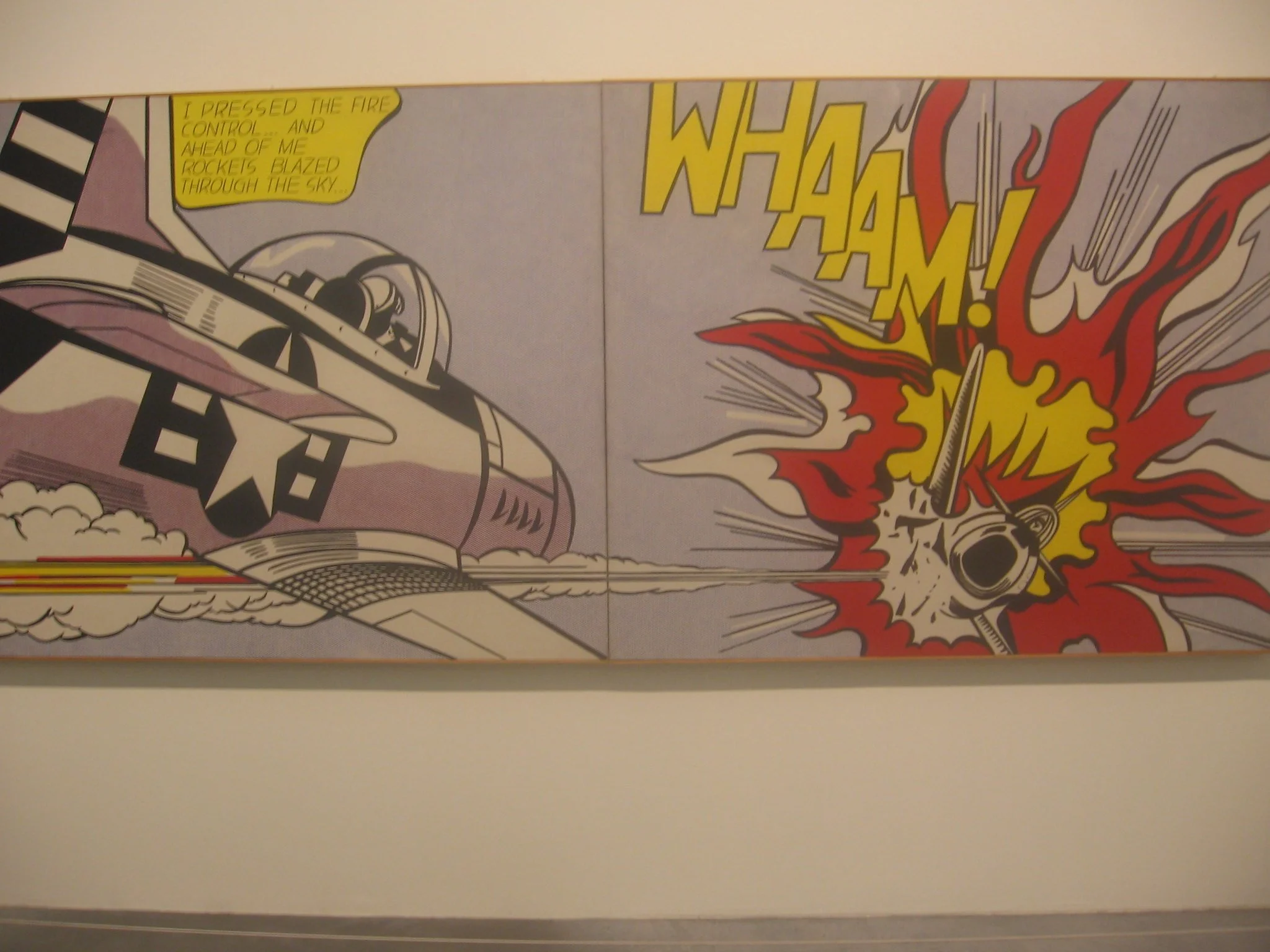

Lichtenstein often ridiculed art, such as the spontaneous splattering of paint typical of abstract expressionism, as evident in "Whaaam!", where the serious subject of aerial combat was reduced to a portrayal reminiscent of comics, lacking greater emotional charge.

The downed fighter jet appears as though painted by an abstract expressionist. It was Lichtenstein's mode of expression, and through his satire of art, despite its deep ties to the conventions of pop art and popular culture, he sought to reveal emotional emptiness in his own way.

We can say that breaking taboos was a phenomenon widely visible in all areas of artistic expression in the 1960s, not only in conventionally understood pop art.

Andy Warhol and his Camouflage

French art critic Gérald Gassiot-Talabot described Warhol's art in 1964 as a celebration of dark mysteries in an absurd world, where empty life implies poisonous preserves, where social assurances do not protect against sudden death, and where theoretical progress of humanism and respect for life allow for electric chair torture or gas poisoning.

Warhol's art certainly fits well in the times it was created, revealing the face of popular culture and modern society, blending anxiety with sadism — which undoubtedly appears to be one of the complexes of the 20th century.

Andy Warhol's works primarily convey an atmosphere of fragility and uncertainty — an atmosphere of accidents, electric chairs, images of the suddenly widowed Jacqueline Kennedy, and criminals hunted by the police.

This description of the atmosphere in Warhol's works also touches on an important issue that has sparked much controversy surrounding pop art, namely — whether artists of this circle praise or criticize consumer civilization.

In most cases, we can say that the painters refrain from giving a clear answer "for" or "against." They are both accomplices and inquisitors who, on the one hand, opportunistically support the existing conditions, but on the other hand, evaluate them coldly.

Andy Warhol, Orange Car Crash Fourteen Times, 1963. Photo: Gwen Fran via Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0

With a characteristic blend of mockery, naivety, and moral indifference, Warhol spoke in 1966 in his most extensive and honest interview:

“The reason I’m painting this way is that I want to be a machine, and I feel that whatever I do and do machine-like is what I want to do“

“The pop artists did images that anybody walking down Broadway could recognize in a split second — comics, picnic tables, men’s trousers, celebrities, shower curtains, refrigerators, Coke bottles. All the great modern things that the Abstract Expressionists tried not to notice at all.“

Warhol always felt representative of the United States in his work, but he was never a critic of the social situation because his aim was never to pass judgment. He merely used what was happening around him as material and painted subjects he was most familiar with. In the same interview, he said about America:

“What’s great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest customers buy essentially the same things as the poorest. You can be watching TV and see Coca-Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coke, Liz Taylor drink Coke, and just think, you can drink Coke, too“

Since Warhol was not the type of artist to comment on reality, he would not have minded if, due to the spread of the screen printing technique, the viewer could not distinguish his works from those of other artists.

It may also suggest that the key to understanding Warhol's work could be the concept of camouflage. He depicted dramatic scenes coldly, avoiding revealing his opinion. Additionally, in his work, he often distorted reality, for instance, abstractly reproducing the colorful face of an actress to distort her beauty.

So, in his art, we are dealing with a phenomenon of aesthetic indifference reminiscent of Duchamp, intensified by the sense of the temporality of the object, which is associated with the concept of packaging (something we open and discard).

In his work, Warhol treated what he depicted as an object of obsessive tautology or ironic fetishism, often simplifying it into the repetitions of the same motif. He frequently profaned artworks with deep traditions, such as the Mona Lisa, dating back to the 16th century.

His desacralizing collage of a cheap reproduction of the Mona Lisa encapsulated in the piece "Four Mona Lisas," served as a clear commentary on mass civilization of reproduction. Without this context, his works would simply be incomprehensible.

Furthermore, the repetition of image arrangements, devoid of framing and clear compositional endings, distinctly evokes the atmosphere of a printing press hall — speed, efficiency, and unlimited production. It alludes to a system in which each copy was untouched by human hands.

The more trivialized through tabloids and newspapers were the faces of Marilyn Monroe and Jacqueline Kennedy, which Warhol explored between 1962 and 1964 after the death of the former and the tragedy of the latter, the more striking was the temporality of both faded idols of the United States.

The repetitions in Warhol's works not only depict stereotypicality and similarity, suggesting that everyone thinks the same, but also reveal that within humans — regardless of the pursuit of novelty — lies the dark temptation of tormenting returns to past nightmares. As he stated, mass media programs us to feel a certain way.

“My fascination with letting images repeat and repeat or in film's case 'run on' manifests my belief that we spend much of our lives seeing without observing”

Photography plays a significant role in Warhol's works. Hand-picked authentic press photos shock primarily through depersonalization, affecting both their photographers, subjects, and broadcasters. This depersonalization also holds the key to deciphering Warhol's art, which was characterized by impersonality — his art aimed to represent anyone, every person who could be, for instance, a statistical victim of a catastrophe.

Andy Warhol, by stripping art of its imprint of personality and depriving it of its subjective articulation of reality, turned it into a tool for another action — the literal recording of facts.

In this way, the impersonality and camouflage in Warhol's work become evident because the viewer looking at Warhol's repetitive images cannot delve into their depth and see the perspective.

Additionally, it's worth mentioning that the criminals in Warhol's paintings gaze apathetically, and the faces of actresses are devoid of expression, making them elusive, unlike in classical portrait painting, which is often filled with psychological content.

The resignation from deeper insights into the perception of the other person was an inherent characteristic of American pop art. Warhol suggested that the aesthetics of calmly contemplated paintings in museums could not equate to the new, dynamic aesthetics derived from photography.

Andy Warhol, since 1963, delved into non-plastic disciplines primarily focusing on film. For a while, he directed musical shows, worked as an author of abstract films for television, and was one of the first to creatively utilize videotape.

Soon after, Warhol directed his activities in such a way that he became one of the most controversial manifestations of the commercialization of art, one that is ruthless and spares no means.

He became one of those individuals who, on the one hand, play their games with exclusive circles of collectors, and on the other hand, appeal to the inclinations of the mass audience.

Warhol was one of the sharpest participants in pop art at a time when the movement was a conscious commentary on popular mass culture within Anglo-Saxon civilization. However, despite his privileged position, or rather because of it, the artist simply became entangled in certain arrangements that prevail within the narrow confines of the elite.

The primary goal of pop art was to keenly embrace life and react particularly sensitively to its transformations.

However, pop art largely lost its organic connection with everyday life, which Claes Oldenburg proclaimed years ago in the previously quoted manifesto "I am for an art that takes its form from the lines of life itself, and is heavy and coarse and blunt and sweet and stupid as life itself."